Translated by Fal Azevedo

For the first time in Brazilian history, the race for the highest post of the country’s executive power had three female competitors. During the first round of 2014 elections, candidates Dilma Rousseff (Workers’ Party – PT), Marina Silva (Socialist Brazilian Party – PSB) and Luciana Genro (Socialism and Freedom Party – PSOL) had, together, 67 million of the 104 million votes, which equal 64.5% of all votes. Among the four leading candidates, three were women. However, what exactly did that mean? Is Brazil becoming more politically inclusive towards women?

Luciana Genro was the only female presidential candidate who spoke openly about issues like abortion and LGBT rights, positioning herself as a firm supporter of those rights. Marina, a candidate linked to the Christian segment - the most vocal against SRHR, and overtly against abortion - quickly erased mentions to the issue from her government plan, saying they had been mistakenly put there by her staff. Dilma Rousseff had, as early as 2010, agreed to not presenting any kind of abortion-decriminalization bills to Congress. Electing a woman for the second consecutive time seems to have changed very little of Brazil’s political culture.

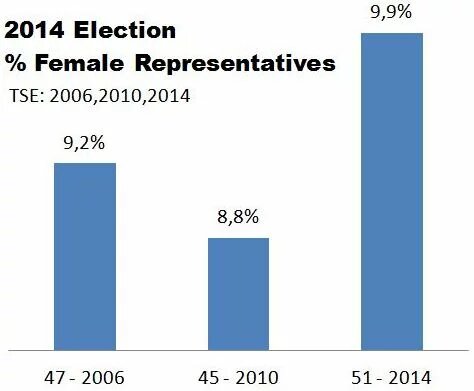

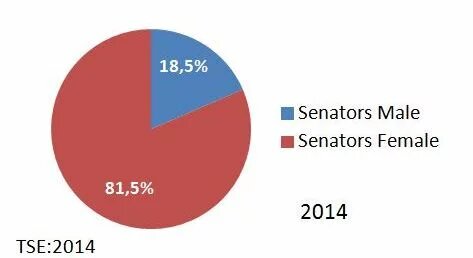

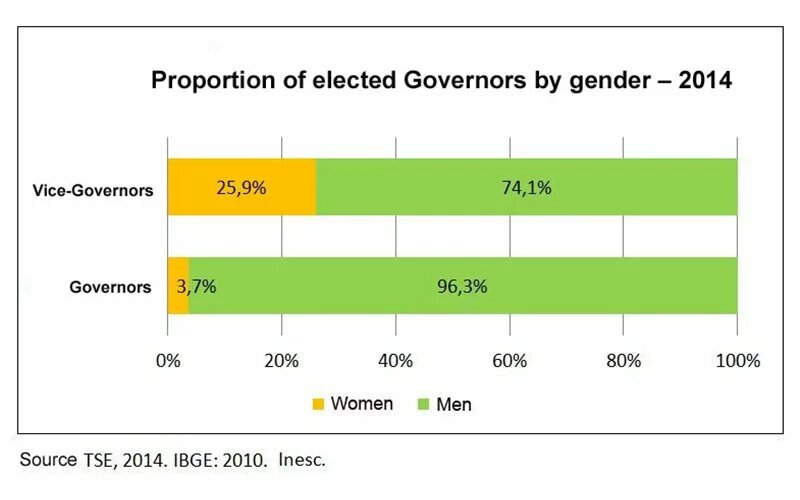

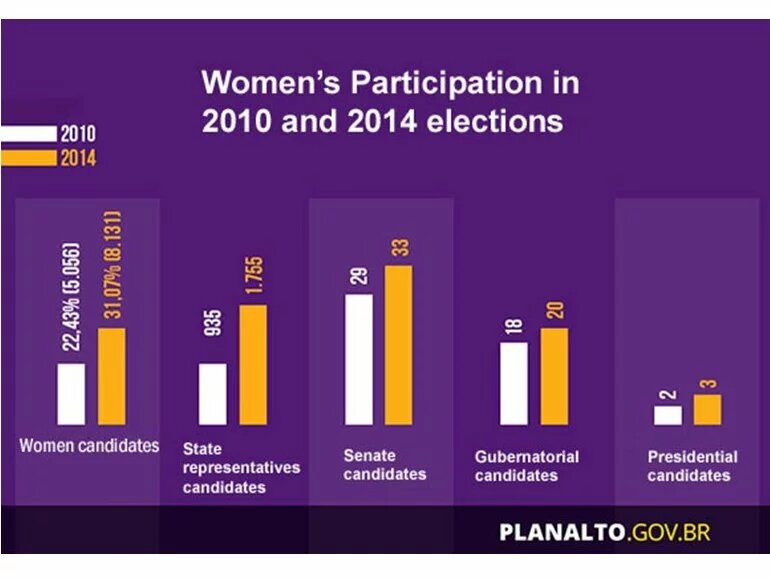

The participation of women as protagonists in politics is still far from representing the composition of Brazilian society. The number of female candidates has grown in the last elections, from 935 in 2010 to 1755 in 2014. Nevertheless, women are still underrepresented among the elected. The current Congress has only 51 women representatives, which mean 9.9% of the 513 congresspersons - just one percentage point above the previous period. In Senate, there are only five women. In 12 states, women representatives were not even among the 10 most-voted candidates. In four states, not even one woman has been elected state representative. In all 27 Brazilian states, including the Federal District, only one woman was elected Governor. The underrepresentation is even more blatant when we break down data also by ethnicity. Brazilian Congress is still mainly white and male, which means that progress is very limited.

This elections-participation progress is due, in great part, to the implementation of an Affirmative Action-like bill (Law No. 0.100/1995), which determined that a minimum of 20% of each party or coalition’s candidates should be women. In 2009, after an amendment to the law, it was determined also that the Parties’ Fund be used in the creation and upkeep of programs to promote and divulge women’s political participation. This law has been in existence for 20 years, a time during which the country has undergone five general elections, not to mention municipal and state elections, also with legislations in effect since 1997 and 2009. Today the minimum percentage is 30%. In spite of that, it was only in 2012 municipal elections that parties finally began fully respecting the minimum quotas legislation, due to the reforms made to 2009 law and to the warnings from the Electoral Justice that some of the male candidacies would be impugned in order to keep the 30%-70% proportion. According to Patrícia Rangel, who works for the Feminist Center for Studies and Counseling (CFEMEA), so far the parties have yet to invest either financial or political resources in female candidacies. In order to observe the law and avoid problems following inspections, most parties put up women candidates “just for show”, and even then, remain limited to the formal and numerical aspects of the law.

In a survey carried out by Interparliamentary Union (UIP), comparing the numbers of seats occupied by women in Houses of Representatives around the world, Brazil reached the 131st place among 189 countries. That is the lowest number in all of South America.

The “macho culture” sees it as normal to emphasize some of the elected women’s physical attributes instead of their political positions or the groups they represent. Recently in O Globo, the second largest newspaper in Brazil, one of the pieces had the title “The beautiful ‘freshwomen’ of Congress” and described how the young new female representatives attracted the attention of Congress veterans because of their beauty. At one point the newspaper highlighted the fact that one “congresswoman goes to the gym regularly and has adopted the latest celebrity diet […] ‘I’m a big fan of Chanel. Which woman isn’t, right?’”. What seemed to matter most were not her political background or plans for her legislature, but her physical traits, something utterly unimaginable when the featured representatives are male. Can anybody fathom a news piece with highlighted information on favorite fragrances, hairdressers or something of similar nature written about a politician such as former president Lula da Silva, or even about Dilma Rousseff’s vice-president Michel Temer?

Without relevant legislative seats or political influence, much of the progressive feminist agenda is seriously compromised. At the same time, changing this is also a task to be undertaken by the entire Brazilian society. According to a 2013 survey made by IBOPE and Patrícia Galvão Institute, 74% of interviewees agree that democracy’s sustenance depends on female participation in power positions, and 78% believe that half the candidates in the list presented by parties should be female. Still this affirmation of women’s relevant role in politics does not translate into actual votes. In the most recent legislature, all data and analyses show that the current Congress is the most conservative of the last 30 years, and predict negative impacts on already-conquered women’s rights, with regressions in some areas, namely sexual and reproductive rights.

Congress’ current president, representative Eduardo Cunha, managed to unearth his formerly failed bill that creates “Heterosexual Pride Day”, and is still trying to pass another one, which provides for up to ten-year prison sentences for doctors who help women abort. Yet another bill, PL 7443/06, intends to put abortion in the category of heinous crimes. Besides, Cunha also presented the bill 6033/2013, which forbids the morning-after pill as a prophylactic measure in sexual assault cases to avoid the risk of an unwanted pregnancy, which goes against one of the procedures already adopted by the national public health system. It is important to note that bills such as these are supported also by female representatives.

According to an analysis made by CFEMEA on 2014 elections, only three of the elected governors’ government plans mentioned any action explicitly directed to the interruption of pregnancies and only two had any mention at all to the term SRHR. Where health and SRHR in general are concerned, all plans reaffirmed the female roles of mother and caregiver, that is, they were all centered on prenatal accompaniment, building of maternity hospitals, humanization of mothers’ postnatal treatment, strengthening of programs for young mothers etc. The data analyzed by CFEMEA show “the lack of political strength to develop projects which present the gender inequality as one of the central and, up to this point, insurmountable problems of the democratic agenda”.

The “political strength” is composed of many elements. One of them is monetary: without funding inside the parties, women will not be able to compete on equal terms for the votes they need. Another one is the lack of commitment of Brazilian society to being truly more inclusive and to acknowledge the importance of having women in relevant positions in the legislative and executive branches of government, notwithstanding the fact of the current president being a woman. Another important point is the need for a political reform that places gender equality as one of its main axes, thus modifying the power balance within the Brazilian political system.