Translated by Fal Azevedo

Even though Brazil’s recent history shows progress in terms of reducing the number of people living in extreme poverty; of raising schooling and of adopting affirmative action policies to protect minorities, there are still huge inequalities between men, women, black and white people in the country. For black women, the situation is the harshest of all, for they suffer double discrimination – that comes from gender and ethnically based prejudices.

The reality of poor quarters and slums (favelas) depicts these unfair relations, and those places are usually historically represented as exotic, precarious, with “invisible” residents, and also devoid of safety. On the other hand, it is currently possible to identify leaders and groups that deconstruct those perceptions, highlighting the complexity, diversity and beauty that exist in those spaces, raising the appreciation for a culture of plain rights, one that fights against racism and sexism on its essence. These movements are made by people like Taís, Gilmara and Jéssyca, who, while still in their twenties, are already main actors of a paradigm shift that is happening; one in which the black identity and the appreciation of women are part of their practices, and are usually multiplied wherever they go.

Popular and Critical Communication

Taís de Amorim, Gilmara Moreira and Jéssyca Liris are among the 90 students of the audiovisual course offered by Espocc – Popular School of Critical Communication, which, since 2005, has invested in the formation of people on affirmative advertising. The competition to study there is fierce and, in 2014, Observatório de Favelas (Slum Observatory), which runs the school in partnership with UFRJ (Rio de Janeiro Federal University), had 300 applications from all over the city of Rio, 60% of them from women. Until now, about 900 students have graduated, and approximately 55% among them are women.

For Taís – a girl born and raised in Vidigal, a south-side slum in Rio -, who’s recently graduated in Journalism, the decision to go to this school stemmed from the desire to use communication and advertising as means to strengthen human rights, especially those of people who, like her come from slums. Gilmara’s motivation is very similar. Resident of Complexo do Alemão (“German’s Hill Compound”, in a loose translation), one of the largest slums of the city’s west side, and a member of Diálogos/Espocc advertising agency, she graduated in Advertising three years ago, in a university located in Ipanema, one of Rio de Janeiro’s most exclusive – and expensive - neighborhoods, and she says that in her college there were “no blacks, no poor people, no slum residents”.

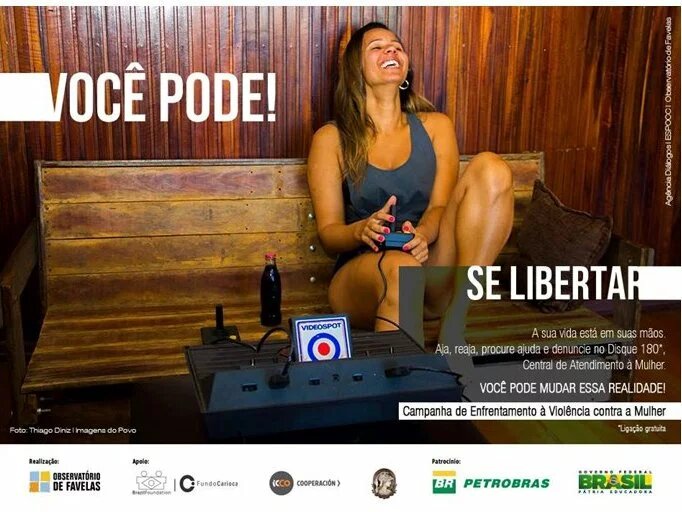

Espocc’s job, though, is not only about giving its students the tools necessary to make a slums-oriented communication. It is a process of fighting for a model of city, one that is capable of defying the dominant representations, based primarily on poverty, scarcity and violence. Another challenge is to also try to steer clear of the folkloric characterizations that always associate slums to samba and gangsterism. According to Taís, the most important thing in the school is the gathering of many different people who reflect on the city of Rio, who share a life in which their rights are constantly violated, but who are seeking for solutions to that problem. One example is the “Você pode” (You can) campaign, created by Diálogos agency for the International Women’s Day, to promote and strengthen Disk 180 (Call 180), a federal government initiative to stimulate calls denouncing violence against women. “We didn’t want to show women looking miserable. Every campaign that deals with gender violence always features sad, crying women,” Gilmara explains. So, their campaign chose empowering women instead, using images of them doing all kinds of activities and phrases like “You can change your story; you can be more than you think”.

Power to overcome racism through hair

“My process of truly identifying myself as a black woman also occurred through my hair, when I decided to stop having it cut and using chemical relaxers,” says Jéssyca, who, besides studying at Espocc, is also a member of the Black Power Girls Collective, with over 53 thousand fans on Facebook. The group was created in 2012 and consists of nine black women, with ages ranging from 17 to 31, who have chosen to keep their natural, curly hair, and who promote educational activities in order to further the debate on white-oriented Brazilian beauty patterns. The event has had three editions, gathering 300 women in activities that have to do with fashion, dance, music and afro-Brazilian poetry. One of the workshops is called Touch your hair. “We ask the women: which adjectives have been used to talk about your hair? Steel wool-like, hard, stinky… then we take what they tell us and how each one really feels about it, and then you see that a girl might think her hair is soft, but other people say it’s hard. And so we start breaking apart these harsh words we hear about our hair. Our hair grows upwards, it is not heavy, it’s not hard: it’s beautiful,” told Jéssyca.

The movie Kbela: adapted from the autobiographical short story Mc K-bela written by the movie director, Yasmin Thayná, it narrates the construction of a black woman’s identity, using her kinky hair as its central theme. “I came to prepare the cast and wound up as part of the movie. It was a liberating, transforming work, a turning point, because we shared what is common to us all, and it strengthened an identity that is undermined and repressed all the time”, explained Taís. The results of the survey “What national movies look like: a profile on Brazilian cinema actors’, directors’ and writers’ genders and ethnicity (2002-2012)”, carried out by the Affirmative Action Multidisciplinary Studies Group (GEMAA) of UERJ (Rio de Janeiro State University), show that over the last ten years, black women have been only 4.4% casts of the main national feature movies. Kbela, to be released in August of 2015, has been funded by an online crowndfunding, and its production crew of 48 people is 90% female, more than ten of them black.

To Gilmara, leaving her hair natural was fundamental in reaffirming her identity and also in taking a stand against racism: “I arrived in Ipanema with my curly hair, telling people I lived at Complexo do Alemão. People began asking themselves what I was doing there. That wasn’t my turf; I just went in and put my foot on the door. I felt the teachers looked at me in a different way, but I was the student who was always at the dean’s office door, picking fights”. Gilmara also believes that this process ends up working as a new model of aesthetics and attitude to other people: “My little cousin saw me with natural hair and noticed her hair was just like mine. ‘You are pretty, and I can be pretty too’. My aunt says that now she has a mini-activist in her home. When you put yourself out as a resistance symbol, you exert influence on other people”.

Outings for coexisting in the city, looking for the ensuring of civil rights

Taís believes that the use of different aesthetics and languages lead to dialogues with more people, and to assure rights: “I watch human rights discussions, political discussions, which are quite cryptic. Many times, the people who have their rights violated do not want to discuss politics, because the language used to approach the issues is almost impenetrable, very different from their own. So what we’ve set out to do with Kbela, Espocc and Cinedadania [a workshops and debates project, which uses audiovisual tools] is talking about racism and civil rights violations, and to spread the knowledge about those rights, through a more relatable language. We try to open new roads through entertainment; to use mass culture in order to approach deeper questions”.

To Gilmara, it is necessary to change the way people live together in the city in order to strengthen civil rights: “As Jéssyca says, my body is a place of resistance. I will take it wherever I want, wherever I can make a difference. I don’t want to just be in the slums; I do want to communicate with the slums, but with places outside them too, because I want people to become less and less uncomfortable with my presence in other places”.