Gender equality advocates in Kenya are grappling with growing popular notions that the focus on girls and women's rights, since the Nairobi World Women's Conference in 1985, has alienated and disenfranchised boys and men. This abrasive sentiment attempts to explain the symptomatic expressions of negative masculinities that have culminated in unabating gender and sexual violence, declining transition rates for boys in tertiary education in professional disciplines, increased alcoholism, and self destructive social behaviour among men in some parts of Kenya. The illustrations by Nduhiu Change seek to summarise the findings of a study conducted by the HBS Nairobi Office in collaboration with a masculinities researcher, Anzetse Were, in September 2014 to February 2015. The study sought to establish the perception, effectiveness and the outlook of masculinity discourse and male centric interventions within the gender sector in Kenya. An executive summary of the study can be downloaded here (PDF).

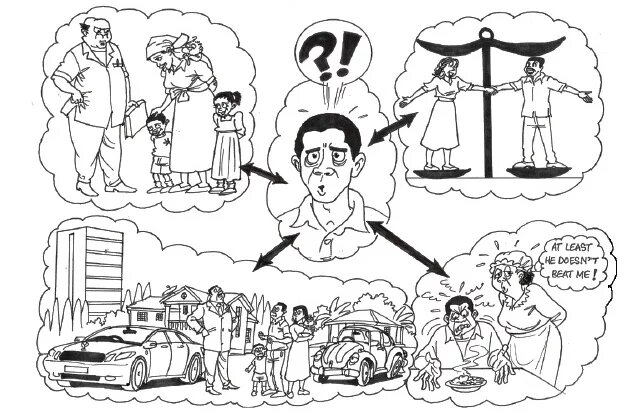

After decades of work toward women and girl's empowerment, there has been little room to openly re-define masculinity. Today's men are formally taught about justice and equality, but lives in a world order that preserves male domination. What, then, does it mean to be a 'good man'? Some say being a good man means benevolent autocracy in the home, with the spouse and children being subordinate. Others aim for economic success and political power; while others argue that a good man simply does not hit a woman (here, violence implies physical abuse only). Yet, through educational, social and legislative re-socialisation, some men begin to understand that gender equality envisions a world where all persons, regardless of sex, race, age, etc can access opportunities and resources with no preference or privilege assigned to any given group. What a confusing world men live in!

Girls' rights programming, particularly affirmative action initiatives have improved the access of opportunities and resources by girls and women. Conversely, the prevailing status of male domination means that boys could become complacent and opt to blame dysfunctional masculinity on women's empowerment. In Kenya, this narrative is picking up momentum and driving debates about "what really is ailing masculinity today"? Youth empowerment projects and peace initiatives that targed idle boys or men aim to address this apparent complacency.

Following the world women's conference in 1985 (Nairobi) and 1995 (Beijing), priorities were set for women and girl's empowerment and gender mainstreaming. Traditional funding for this work has been directed to feminist actors and women's rights NGOs. Today, with the advancement of gender discourse, programming around masculinities is gaining traction. However, perhaps due to long term feminisation of gender work, there seems to be hesitation among some donors to directly fund masculinities work. Further, feminist action is premised on the fact that patriarchy oppresses women. In the last couple of decades, there has been growing awareness that patriarchy also affects men negatively; hence masculinity advocates are seeking visibility and spaces to contribute to gender justices discourse. Conventional funders of gender work are beginning to recognise the need to program on masculinity work.

Sometimes the strongest proponents of patriarchy are women, due to generational conditioning of gender norms that become ingrained in culture. One way that gender stereotypes are being dismantled is through re-socialising men toward an attitude change. Harmful cultural practices such as female genital mutilation are best defeated when those who stand against such practices are those perceived to demand it - in this case, men.

Women's rights advocates recognise the need to involve men in gender equality advocacy but have serious doubts and mistrust about men's motivations. Aware of the fact that men still dominate most of society's power and decision-making structures, women's organisations often have to find a middle ground between engaging men in the journey towards women's empowerment and gender equality while battling the possibility that men can "take over" and tip the balance in their favour again - potentially destroying the gains women's organisations have fought so long to accrue. It's a fragile tight-rope many feminist organisations are walking.

At time, there is hypocrisy in rights activism. The cartoon here depicts a scenario of a male gender-equality advocate who knows all the rights things to say in public, giving the impression that he believes in gender equality. But such a rhetoric is not reflecting his actual life! This also applies to human rights practitioners who think of their work as a career rather than as a genuine quest for social justice. Gender mainstreaming, which was a strategy introduced in the Beijing Platform for Action to enhance gender justice in governance is often defeated by this hypocrisy. It is important that: 1) Masculinities organisations realise that even male activists are still on their own journey toward transformation and are not "perfect men", and 2) Women's organisations must actively foster the internalisation of the message of gender justice; this internalisation should be an on-going process within female organisers and their male allies.