Biologically, women are more likely to be adversely affected by the toxins in plastics. Traditional roles, inequality, and a throwaway culture further amplify these harmful effects, especially in Asia.

Women and men can be exposed to plastic products and packaging. Both can work as formal waste collectors, informal waste pickers, or work in factories that make plastics. Both can unwittingly ingest or breathe harmful chemicals from plastics and disrupt their endocrine system, eventually suffering from infertility, obesity, diabetes, and neurological diseases, among others.

However, there is evidence that the toxins contained in plastics have different effects on women and men due to biological differences including body size and proportion of fatty tissue.

Phthalates, commonly used as a plasticiser, have been shown to block thyroid hormone action and reduce both testosterone and oestrogen levels. In addition, they have been identified as reproductive toxicants for both women and men.

Yet women’s bodies contain more fat than men‚ and therefore accumulate more phthalate plasticisers and other oil-soluble chemicals. The female body is also especially sensitive to toxins during life stages such as puberty, pregnancy, lactation, and menopause.

In 2017, the Nordic Council of Ministers drew up a list of 144 hazardous substances actively being used in plastics for functions varying from antimicrobial activity to colourants, flame retardants, solvents, and plasticisers.

Exposure to these endocrine disruptor chemicals can occur over the entire lifespan of plastic products, from the manufacturing process and consumer contact to recycling, waste management, and disposal.

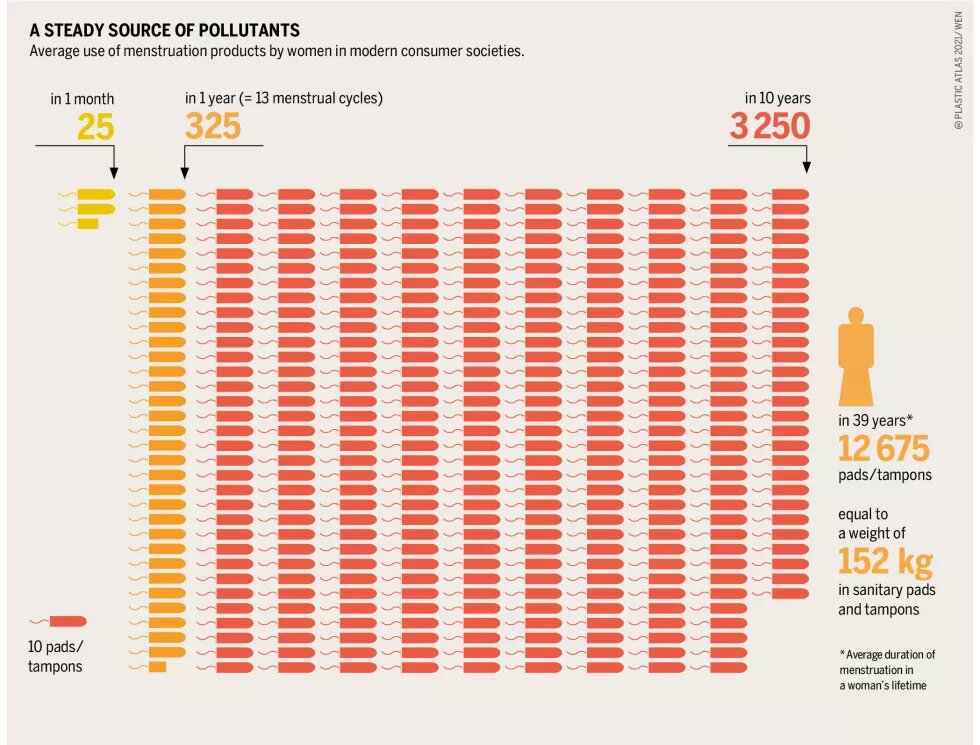

For at least four decades of their lives, women are consumers of specific plastic products supplied as feminine hygiene items, and the major marketing targets for others, such as cosmetics. The world’s feminine hygiene industry is expected to hit US$53 billion in sales by 2023.

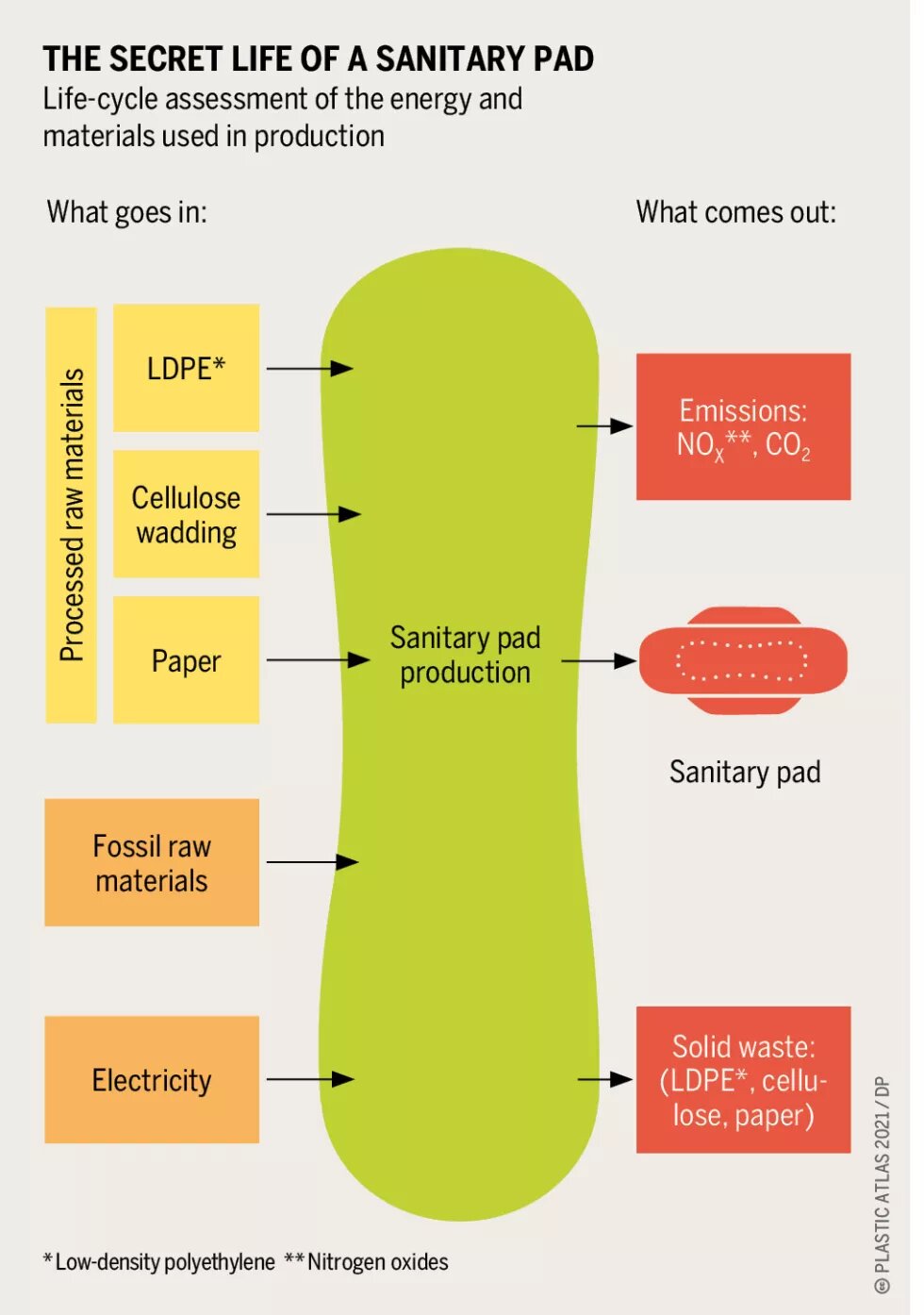

In the UK, it was found that the average woman will use more than 11,000 menstrual products over her lifetime, amounting to over 200,000 tonnes of waste ending up in the country’s landfills and waterways every year. With store-bought sanitary pads comprising 90 percent plastic, mass-produced feminine care products come with a hefty environmental footprint.

By 2015, Asia-Pacific alone accounted for half of global demand for single-use feminine hygiene products, with cities in the region grappling with the enormous quantities of such items discarded in waterways, buried in the soil, or burned in the open.

In addition to biology and the throwaway culture, economic and social roles have made women more vulnerable and exposed to hazards caused by plastics.

In Asia, women’s traditional jobs as unpaid carers and domestic homeworkers bring daily exposure to household plastic products and waste. Meanwhile, as employees, a disproportionate number of women work in industries that expose them to toxic chemicals present in plastics.

Women account for a significant proportion of the informal waste sector in India, the Philippines, Vietnam, and Indonesia. As waste pickers, they are tasked with picking out post-consumer recyclables from dumpsites, and engaged by scrap/junk shops to sort, clean, and perform other repetitive tasks in the plastic recycling process. These types of work expose them to dust and chemicals through inhalation and contact with skin.

Moreover, garment factories in Asia employ mostly women, who become exposed to toxins from the synthetic fibres now favoured by the textile industry and widely used in fast-fashion clothes.

Women working in plastic manufacturing where they are exposed to dust and fumes are more likely to develop breast cancer and experience reproductive problems. They also become unwitting carriers of plastics and associated chemicals when these are transported through the placenta to foetuses.

In many communities, women lack access to knowledge and information about the chemicals in plastics and the impacts on health, and are unable to minimise toxic chemical exposure.

While legislating gender-responsive policies, such as guidelines to protect women as consumers and as workers in the formal and informal waste sectors, could help, more wide-reaching would be a reflection on the role that gender plays in society overall.

Yet even these measures can only mitigate the adverse impacts of plastics and are insignificant in the context of the ubiquity of plastics and persistence of the chemicals they contain.

This article was first pubished by HBS Hong Kong.