Gendered disinformation is a form of identity-based disinformation that threatens human rights worldwide. It undermines the digital and political rights, as well as the safety and security, of its targets. Its effects are far-reaching: gendered disinformation is used to justify human rights abuses and entrench repression of women and minority groups. This policy brief explains what gendered disinformation is, how it impacts individuals and societies, and the challenges in combating it, drawing on case studies from Poland and the UK. It assesses how the UK and EU are responding to gendered disinformation, and sets out a plan of action for governments, platforms, media and civil society.

1. Gendered disinformation is a weapon

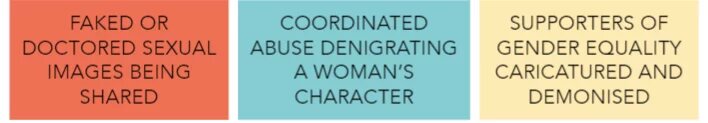

Gendered disinformation is manipulated information that weaponises gendered stereotypes for political, economic or social ends.[1] Examples of gendered disinformation include:[2]

A gendered disinformation campaign is one which is coordinated and targeted at specific people or topics. There are different ways campaigns originate and spread; they may draw on existing rumours or attacks and amplify them inorganically[3], or originate messages which authentic users outside of the campaign then disseminate.[4] Campaigns may be directly state-sponsored, share state-aligned messages, or be used by non-state actors.

Gendered disinformation is often part of a broader political strategy,[5] manipulating gendered narratives to silence critics and consolidate power.[6] It can also intersect with other forms of identity-based disinformation[7] , such as that based on sexual orientation, disability, race, ethnicity, or religion.[8]

2. Gendered disinformation threatens individuals

Gendered disinformation disproportionately affects people of the gender that it targets: making spaces, both online and offline, unsafe for them to occupy. It can be weaponized against anyone: but is often used against women in public life - 42% of women parliamentarians surveyed in 2016 said that they had experienced ‘extremely humiliating or sexually charged’ images being shared online.[9] Gendered disinformation commonly weaponises stereotypes such as women being devious, stupid, weak, immoral or sexualising them to paint them as untrustworthy and unfit to hold positions of power, a public profile or influence within society.[10]

The psychological toll it takes on its targets can be profound, and deprives them of the freedom to exist on social media that in today’s digitalised world is often crucial to people’s professional and personal lives.[11] And it is not only online violence that is a concern: the volume and nature of the threats and abuse means that personal safety is a concern, with those who are targeting women engaging in public scrutiny of everything from their appearance to their work and their private lives to alarming levels of detail and distortion.[12]

3. Gendered disinformation threatens democracy

Gendered disinformation fundamentally undermines equal participation in democratic life, and reduces the space for women to be involved in public life.[13] This in turn undermines the effectiveness, the equity, and the representativeness of democratic institutions.[14]

The reinforcement of negative gendered stereotypes online bolsters misogynistic attitudes to women’s role in the public sphere and in society.[15] And the cost to public life is significant. Women in particular are driven out of public life: those who are already in it leave, feeling it is no longer tolerable or safe for them[16],[17],[18],[19] - and those who remain often distance themselves from engaging with the public through social media.[20] Others are put off entering public life in the first place because they anticipate gendered abuse.[21] In the UK, Black women in public life are 84% more likely to experience online abuse than white women, and are likely to be disproportionately excluded from participating.[22]

4. Gendered disinformation threatens security and human rights

Gendered abuse acts as a vector for bad information.[23],[24] Gendered disinformation is a recognised tactic used by authoritarian actors (including in democratic states) to undermine threats to their power - whether that threat be an individual woman opponent, or a whole movement.[25] For instance, in Pakistan, women journalists who criticise the government are subject to false ‘fact-checking’ and resulting harassment.[26] In many cases, women’s rights, and the rights of LGBT+ people, are depicted as threats to order and national identity and used to foster social divisions, often as part of a wider assault on human rights.[27],[28],[29],[30]

And disinformation can also act as a vector for gendered hate.[31] The rise of incel and far-right communities online feed the stereotypes that women have hidden malicious intentions or are using their sexuality to manipulate men - narratives which then move onto mainstream platforms and gain traction, stoking the hate directed against women in public life.[32] And increasingly extremist gendered disinformation risks legitimising offline violence against women. In the US, online conspiracy theories have fuelled plots to kidnap a female governor.[33] Far-right extremism is a growing threat in the UK[34]: the MP Jo Cox was murdered in 2016 by a far-right extremist,[35] and MPs have spoken out about the continuing threats they receive, including threats of sexual violence.[36],[37] Women journalists in Afghanistan have been killed and threatened, with Human Rights Watch linking this targeting to women journalists ’challenging perceived social norms’.[38] In Brazil, Marielle Franco, a city councillor in Brazil and a critic of the state, was murdered, following which a disinformation campaign about her life circulated widely online.[39],[40],[41],[42]

By reconceptualising women or LGBT+ people as threats to the existence, morality or stability of the state, gendered disinformation risks making violent action taken to eliminate those threats seem permissible within public political discourse - gendered disinformation is a form of ‘dangerous speech’.[43],[44] It uses gendered stereotypes to dehumanise its targets - the ‘out-group’ of women or LGBT+ people - and builds solidarity amongst their attackers.[45],[46],[47] The results can be activists, journalists or politicians being arrested, detained, attacked or even murdered.

5. Gendered disinformation is parasitic, amplifies existing stereotypes and prejudices

Gendered disinformation gains its power by tapping into existing stereotypes and caricatures to evoke emotional responses,[48], gain credibility, and resonate with and encourage others to join in: the intended audience is not only those targeted but wider observers. Gendered disinformation attacking women will often use multiple different gendered narratives to undermine or denigrate their character[49]: particularly to depict women as malicious ‘enemies’, or as weak and useless ‘victims’.[50] Some classic tropes weaponized against women include labelling them as:[51]

‘Language matters’, and is a key instrument in the dissemination of gendered disinformation.[52] Disinformation campaigns in Poland have sought to weaponise and redefine gendered terms in public discourse, through equating the concept of ‘women’s rights’ with ‘abortion’ and ‘abortion’ with ‘murder’ and ‘killing children’.[53],[54] Those who support women’s rights and reproductive rights are attacked online by state-aligned disinformation as stupid, evil and hypocritical, with ‘feministka’ (feminist, diminutive) often used as a term of abuse.[55] Another commonly used narrative used by the state and public institutions is that ‘LGBT is not people, it's an ideology’, from which children and wider society must be ‘protected’.[56]

The impact of these disinformation campaigns that seek to redefine terms is not simply to make people believe untrue things, but to implicitly permit and try to legitimate aggression towards and the limitation of rights of these groups.[57] Towns in Poland have declared themselves ‘LGBT-free zones’ where LGBT+ rights are rejected as an “aggressive ideology” and LGBT+ people face discrimination, exclusion and violence.[58],[59],[60] Women’s rights defenders, including those involved in the Women’s Strike protesting restrictions on abortion, have faced detention and threats, which they link to ‘government rhetoric and media campaigns aiming to discredit them and their work, which foster misinformation and hate’.[61] These assaults are exacerbated and legitimised by gendered disinformation.[62]

The same weaponised stereotypes that are common across gendered disinformation campaigns occur in UK political discourse online: that women are devious, evil, immoral, shallow or stupid.[63],[64] A woman MP was targeted while she was pregnant because of her pro-choice politics, with graphic anti-abortion posters being put up in her constituency and a website which called for her to be ‘stopped’.[65] Other cases include conspiracy theories being shared accusing a black woman MP of editing video footage and lying about racism that she faced,[66] and a fake BBC account ‘reporting’ a false interview with a party leader about sexism.[67],[68] Journalists in the UK targeted for their reporting have experienced misogynistic abuse online echoing these gendered tropes, in particular seeking to undermine their legitimacy and autonomy: using descriptions like ‘silly little girl’ or ’puppet’, making sexualised comments or threats, or attributing malicious motives to them.[69] Women in public life who focus particularly on women’s equality face similar attributions of malevolent intent, and their feminist motivations distorted or fabricated - such as facing accusations of seeking to ‘emasculate men’.[70]

6. Gendered disinformation can be difficult to identify - for humans and for machines

Although ‘falsity, malign intent and coordination’ are key indicators of gendered disinformation[71], identifying these factors in individual pieces of content is challenging and sometimes impossible.

Human observers may struggle to identify gendered disinformation, which will often appear more like online abuse than ‘traditional’ disinformation. Often disinformation is conceptualised as lies or falsehoods: but the bases of gendered disinformation are stereotypes and existing social judgements about ‘appropriate’ gendered attributes or behaviour, and so may not be straightforwardly false. It may use true information, misleadingly presented or manipulated, unprovable rumours, or simple value judgements (which cannot be classified as ‘true’ or ‘false’) to attack its targets.[72] When a campaign is inauthentic (e.g. through false amplification using paid trolls or bots) can also be difficult to definitively and rapidly identify. Gendered disinformation can evade human moderation: it uses in-jokes and coded terms only immediately understandable to people with a comprehensive understanding of the political context of the campaign and its targets: while global platforms fail to invest in this needed in-country expertise.[73],[74]

Technology has similar challenges. Gendered disinformation exhibits ‘malign creativity’, using different forms of media and ‘coded’ images and terms that seem innocuous or meaningless without context.[75] This may include using pictures of cartons of eggs to taunt women as being ‘reproducers’[76]; using nicknames or terms for someone that are only used within that campaign, or swapping the characters used in common terms of abuse (such as ‘b!tch’)[77]. As a result campaigns can evade automated detection and filters based on particular keywords or known images.[78] And gendered disinformation may not always appear to denigrate a certain gender, but still reinforces harmful stereotypes: disinformation weaponizing the view of women as ‘weak’ may co-opt the language of seeking to protect women, especially from violence. As such, it can appear in form similar to counterspeech, and understanding of the wider context, inaccessible to a machine, is needed for identifying it as disinformation.[79]

7. How far are the EU and UK ready to meet this challenge?

The UK and the EU are both preparing to implement greater regulation of digital platforms, to try to tackle many forms of online harms.[80] New legislation is a positive first step - but cannot prevent gendered disinformation on its own.

The UK Online Safety proposals, published this year, have potential: they will implement a regulatory framework which enables greater scrutiny of platforms’ systems and processes. This may help to reduce the enforcement gap that exists both on action being taken on illegal abuse online and on ‘legal but harmful’ abuse,[81] by holding platforms to account for being clear and consistent in enforcing the processes they have for curating and removing such content.

However, there remains concerns about its efficacy. Firstly, only a select few platforms will have responsibility to make systematic changes on ‘legal but harmful’ content - the category gendered disinformation is likely to often fall into - and many of the more radical forums risk being out of scope.[82] The changes even the largest platforms will be expected to make are primarily to enforce clear terms of service, rather than to take proactive measures to curb gendered disinformation.

Secondly, the proposals seek to protect content of ‘democratic importance’ - content which relates to a current political debate, which platforms may have a higher duty to protect from takedown. Gendered disinformation frequently appears to be related to political issues, such as women's political decisions, meaning that it could end up with special protection from removal.

In Poland, government legislation cannot be the solution. Human rights activists in Poland[83] and around the world are vocal in condemning gendered disinformation, but the disinformation serves the interests of the ruling party. Indeed, in January Poland proposed a new law which would fine social media platforms if they removed any content that was legal under Polish law or banned users who posted it.[84]

When the EU brings in the Digital Services Act, there is the potential that this will include obligations on platforms to make changes to their systems to reduce the spread of content that could include violent content such as gendered disinformation.[85] However, these will need to be substantive obligations to reduce gendered disinformation - as it stands, only illegal content is likely to be in scope, restricting the degree to which meaningful action can be taken.

The recently published guidance on strengthening the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation is more promising.[86] The expansion of the focus from ‘verifiably false or misleading information’ to ‘the full range of manipulative techniques’ means that emotional, abusive or coded information that is used in gendered disinformation campaigns comes within scope.[87] What is required of platforms is also more robust: for instance, that signatories produce a ‘comprehensive list of manipulative tactics’ that are not permitted. Greater transparency on content curation, ndependent data access and pre-testing of design changes, all provide a crucial iterative knowledge base on which responses to gendered disinformation can be built. However, the guidance fails to acknowledge the disproportionate gendered impacts of many of the ‘manipulative techniques’ it describes (such as deepfakes), and risks overlooking the need for specific action to minimise the gendered weaponisation of these tactics.

There is a need for action to protect gender equality and freedoms at a more fundamental level. The EU and other international institutions should also resist the threat of the definitions of established rights for women and LGBT+ people being altered or changed through gendered disinformation campaigns.[88]

8. A Manifesto for Change

To reduce the impact of gendered disinformation, there are three stages interventions need to be targeted at: with progress on each reinforcing the others. Proposals to disarm gendered disinformation should identify how they will contribute to each of these factors:

We need to move from a reactive and narrow approach to a proactive and intersectional approach to gendered disinformation.[89][90] Digital hate and disinformation campaigns move across platforms, use coded language and incorporate both formal and informal networks, meaning they can quickly evolve in response to reactive measures.[91] Though platforms should continue to develop and invest in empowering and supporting users in controlling their online experiences and reporting abuse or harassment[92],[93], responses to gendered disinformation cannot be limited only to these measures.[94]

This means identifying the factors which increase the risk of different forms of gendered disinformation in different contexts and taking steps to minimise them, rather than waiting for campaigns to occur and then trying to retrofit an effective counterattack. It means moving from a model where women shoulder the burden of reporting individual attackers to one where information environments are redesigned to reduce the risk of gendered disinformation.[95]

Policymakers, platforms and civil society need to create early warning systems through which gendered disinformation campaigns can be reported and identified. Initiatives such as the EU Rapid Alert System which enables rapid coordinated international responses from governments and platforms in the face of an evolving threat of disinformation could be deployed in response to newly identified gendered disinformation campaigns.[96] However, as gendered disinformation is a tactic used by authoritarian states, we cannot rely simply on governments to bring about change.[97]

Below is a compilation of actions that can be taken by different stakeholders to proactively reduce the incidence, spread and impact of gendered disinformation. Together, these make up a manifesto for change: to better protect individuals, democracy, security and human rights.

PREVENT: how do we make gendered disinformation less likely to occur?

Governments/international institutions

- Gendered disinformation is a weapon

- Gendered disinformation threatens individuals

- Gendered disinformation threatens democracy

- Gendered disinformation threatens security and human rights

- Gendered disinformation is parasitic, amplifies existing stereotypes and prejudices

- Gendered disinformation can be difficult to identify - for humans and for machines

- How far are the EU and UK ready to meet this challenge?

- A Manifesto for Change

- Maintain and stand up for established definitions of rights and liberties for women and LGBT+ people which are at risk of becoming weaponised[98]

- Legislate to ensure that platforms are meeting certain design standards, ensuring a gender sensitive lens[99]

- Support programming to combat gender inequality and gendered oppression[100]

- Members of political parties should ensure that campaigning does not exacerbate gendered stereotypes or attacks other candidates in gendered ways[101]

- Introduce standards for political campaigning and politicians to uphold which are gender-sensitive[102]

- Establish gender equality committees to assess legislation for any potential discriminatory effects[103]

- Ringfence a portion of taxes levied on digital services to fund initiatives to combat online gender-based violence[104]

Platforms

- Test how design choices affect the incidence of gendered disinformation and make product decisions accordingly[105]

- Make data more easily available to researchers to support the tracking and identification of gendered disinformation[106]

Media

- Ensure reporting on people in public life is gender-sensitive and does not reinforce harmful stereotypes[107]

Civil Society

- Support greater visibility of digital allyship by men to create a cultural shift of non-tolerance of abuse in online communities[108]

- Engage with stakeholders internationally to build research and understanding of gendered disinformation[109],[110],[111]

- Ensure research on disinformation and hate online is carried out with an intersectional gender lens

- Increase research and investigation into gendered disinformation in the Global South to balance the bias in research focusing on the Global North [112]

REDUCE: how do we make gendered disinformation less able to spread?

Governments/international institutions

- Build early warning systems as exist to tackle other increasing risks of violence[113]

- Invest in digital and media literacy initiatives[114]

- Recognise that the protection of rights online, including the protection of freedom of expression, requires action against gendered disinformation[115]

- Ensure legislation is flexible enough to dynamically respond to evolving technologies and threats[116]

- Introduce independent oversight of what changes platforms are making and how they are responding to gendered disinformation campaigns[117]

- Require platforms to provide comprehensive psychological support for human moderators[118]

- Introduce measures to disrupt platform’s business models of profiting from gendered disinformation (such as making tax breaks dependent upon platforms’ meeting certain standards of content curation and harm prevention)[119]

Platforms

- Improve processes for running ongoing threat assessments and early warning systems, engaging with local experts[120],[121],[122],[123],[124],[125]

- Facilitate the reporting of multiple posts together[126]

- Empower users to provide context for moderators to review when submitting reports of abuse or harassment[127]

- Improve content curation systems: make changes to content curation systems in order to demote gendered disinformation and to promote countermessaging[128],[129],[130],[131],[132],[133]

- Strengthen terms of service to clearly define different forms of online violence, prohibit gendered disinformation and enforce those terms consistently[134],[135]

- Improve content moderation systems: ensure enforcement by increasing and supporting human moderation[136],[137]

- Employ an iterative reviewing and updating of moderation tools and practices in consultation with experts who understand the relevant context[138],[139] , and update moderation processes rapidly in response to new campaigns[140],[141],[142],[143].

- Share data on how different interventions affect the spread of disinformation and misinformation on their services[144]

- Offer users more information and powers to control responses when their content is being widely shared, and enable them to share these powers with ‘trusted contacts’[145]

Media

- Support digital and media literacy initiatives[146]

- Reporting on gendered disinformation should clearly call it out, and avoid amplifying otherwise fringe narratives [147],[148]

Civil Society

- Engage in countermessaging to promote gender equality as a key tenet of the ideals being weaponised, such as national identity[149]

- Work to identify how international human rights law can be applied by private companies in content moderation decisions[150]

- Coordinate internationally to raise the alarm of new gendered disinformation campaigns and provide workable solutions[151],[152],[153]

RESPOND: how do we lessen the harmful impacts of gendered disinformation?

Governments/international institutions

- Invest in programming which supports people in public life who are targeted by gendered disinformation

- Invest in education for law enforcement on how online abuse works and how they should respond to reports of threats or abuse[154]

Platforms

- Make the process of reporting gendered disinformation clearer and more transparent and include greater support and resources for its targets[155]

- Ensure information and tools for users are explained in clear and accessible language[156]

- Increase user powers to block or restrict content or how other users can contact them or interact with their posts[157],[158]

- Invest in systems which respond rapidly to remove accounts or content, including in private channels[159]

- Introduce automated and human moderation systems specifically designed to identify likely incitements to violence in response to a specific campaign or person’s speech[160]

Media

- Engage with platforms to support fact-checking initiatives to discredit gendered disinformation campaigns

Civil Society

- Carry out research longitudinally to track the long term financial and political impacts of disinformation and chilling effects[161],[162],[163]

- Support people targeted by gendered disinformation through digital safety trainings[164]

- Avoid framing solutions to gendered disinformation as being the target’s job to manage (e.g. by simply ‘not engaging’)[165]

With thanks to Mandu Reid, leader of the Women’s Equality Party in the UK, Eliza Rutynowska, a lawyer at the Civil Development Forum (FOR) in Poland, and Marianna Spring, a specialist reporter covering disinformation and social media at the BBC, for their input.

[2] https://www.disinfo.eu/publications/misogyny-and-misinformation:-an-analysis-of-gendered-disinformation-tactics-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/; https://demos.co.uk/project/engendering-hate-the-contours-of-state-aligned-gendered-disinformation-online/; https://www.beautiful.ai/player/-MSj9MbXLfaRfSreqNeL/Womens-Disinfo-KW; https://speier.house.gov/_cache/files/6/c/6c8eec9e-eadf-4aac-a416-38597…

[3] https://demos.co.uk/project/warring-songs-information-operations-in-the-digital-age/; https://demos.co.uk/project/engendering-hate-the-contours-of-state-alig…

[7] See https://protectionapproaches.org/identity-based-violence for an explanation of identity based violence

[8] Interview with Mandu Reid

[12] Interview with Marianna Spring

[13] https://demos.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Engendering-Hate-Report-… ; https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/malign-creativity-how-gender-sex-and-lies-are-weaponized-against-women-online; https://policyblog.stir.ac.uk/2020/03/23/gendered-misinformation-online-violence-against-women-in-politics-capturing-legal-responsibility/, https://mediawell.ssrc.org/expert-reflections/disinformation-democracy-…

[14] Interview with Mandu Reid

[15] https://genderit.org/feminist-talk/approaching-fight-against-autocracy-feminist-principles-freedom; interview with Mandu Reid

[20] Interview with Mandu Reid

[21] Interview with Mandu Reid

[22] https://www.amnesty.org.uk/press-releases/uk-online-abuse-against-black-women-mps-chilling; interview with Mandu Reid

[32] Interview with Mandu Reid

[34] https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/far-right-still-a-growing-threat-five-years-after-uk-politician-jo-cox-s-murder-by-neo-nazi-1.1242642; https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/europe/hope-not-hate-far-right-th…

[39] https://rioonwatch.org/?p=63454; https://piaui.folha.uol.com.br/lupa/2019/03/25/artigo-fake-news-mariell…

[44] https://www.academia.edu/905194/Genocidal_Language_Games; Interview with Eliza Rutynowska

[46] See https://protectionapproaches.org/identity-based-violence for an explanation of identity based violence

[51] https://www.disinfo.eu/publications/misogyny-and-misinformation:-an-analysis-of-gendered-disinformation-tactics-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/; https://demos.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Engendering-Hate-Report-FINAL.pdf; https://www.beautiful.ai/player/-MSj9MbXLfaRfSreqNeL/Womens-Disinfo-KW

[52] Interview with Eliza Rutynowska

[53] Interview with Eliza Rutynowska

[56] https://www.euronews.com/2020/06/15/polish-president-says-lgbt-ideology-is-worse-than-communism; Interview with Eliza Rutynowska

[57] https://notesfrompoland.com/2021/06/23/lgbt-deviants-dont-have-same-rights-as-normal-people-says-polish-education-minister/; Interview with Eliza Rutynowska

[64] A recent study which looked at abuse directed at international women politicians, including the UK Home Secretary, did not find evidence of gendered disinformation campaigns against her - though found more work was needed to establish the reason for this and what it indicates about gendered disinformation in the UK more widely. This may indicate that high-profile and sophisticatedly coordinated gendered disinformation campaigns are currently less common in the UK. However, there are multiple instances of gendered disinformation being used against women politicians in the UK over many years. - see https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/malign-creativity-how-gender-s…

[65] https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/oct/06/stella-creasy-anti-abortion-group-police-investigate-extremist-targeting; https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/03/london-council-orders-ant…

[66] See also https://inews.co.uk/news/politics/dawn-butler-video-police-stopped-labo…

https://firstdraftnews.org/latest/uk-general-election-2019-the-false-mi…

[68] As well as a satirical article going viral and being taken as authentic claiming that there was ‘harrowing’ footage of her killing squirrels https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/jo-swinson-squirrels-sho…

[69] Interview with Marianna Spring

[70] Interview with Mandu Reid

[73]https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/uploads/documents/Report%20Malign%20Creativity%20How%20Gender%2C%20Sex%2C%20and%20Lies%20are%20Weaponized%20Against%20Women%20Online_0.pdf; https://demos.co.uk/project/engendering-hate-the-contours-of-state-alig…

[76] https://www.wired.com/story/online-harassment-toward-women-getting-more…

;https://www.mediasupport.org/blogpost/digital-misogyny-why-gendered-dis…

[78]https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/media/uploads/documents/Report%20Malign%20Creativity%20How%20Gender%2C%20Sex%2C%20and%20Lies%20are%20Weaponized%20Against%20Women%20Online_0.pdf; https://demos.co.uk/project/engendering-hate-the-contours-of-state-alig…

[81] Interviews with Mandu Reid and Marianna Spring

[84] bbc.co.uk/news/technology-55678502

[88] Interview with Eliza Rutynowska

[95] https://mediawell.ssrc.org/expert-reflections/disinformation-democracy-and-the-social-costs-of-identity-based-attacks-online/, Interview with Marianna Spring

[97] https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/06/07/how-authoritarians-use-gender-weapon/?utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=wp_opinions&utm_source=twitter, Interview with Eliza Rutynowska

[98] Interview with Eliza Rutynowska

[108] Interview with Mandu Reid

[116] Interview with Mandu Reid

[119] https://issuu.com/migsinstitute/docs/whitepaper_final_version.docx, interview with Mandu Reid.

[132] https://www.beautiful.ai/player/-MSj9MbXLfaRfSreqNeL/Womens-Disinfo-KW; Interview with Marianna Spring

[144] Interview with Mandu Reid

[154] Interview with Marianna Spring

[157] https://www.beautiful.ai/player/-MSj9MbXLfaRfSreqNeL/Womens-Disinfo-KW; Interview with Marianna Spring

[159] Interview with Marianna Spring

[161] https://www.mediasupport.org/news/gendered-disinformation-and-what-can-be-done-to-counter-it/; Interview with Mandu Reid

[163]https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/866351/How_to_Guide_on_Gender_and_Strategic_Communication_in_Conflict_and_Stabilisation_Contexts_-_January_2020_-_Stabilisation_Unit.pdf

[164]https://glitchcharity.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Dealing-with-digital-threats-to-democracy-PDF-FINAL-1.pdf

[165] Interview with Marianna Spring