Introduction

Results of the questionnaire:

- Tunisia: December 17, 2010 to January 14, 2011

- Egypt: December 25, 2010 to February 11, 2011

- Yemen: December 18, 2010 to the present

- Libya: February 17, 2011 to the present

- Syria: March 15, 2011

Revolution is a broad church; it is a warm embrace, welcoming, lavish; it is a time of rapture, hope and dreams; it is the festival, the ‘carnival’ as some call it. So many of those who take part in it claim to be happy, to have been reborn, risen again from death. So many have wept for joy.

Revolution is an epic of beatification. Its participants and sympathisers imagine that their lives will be better after it has won out and tyranny has fallen— they will be able to succeed, to build, to achieve—for revolution is like an amnesty, like the month of Haram when no blood may be shed. It is a state of pure solidarity in which those who yesterday were strangers, of every stripe and type and creed, sing in harmony, their sensitivities, the jealousies and resentments that divided them, vanished in the wind. It is an unprecedented state that gives birth to unprecedented: martyrdom and sacrifice, the rise to prominence of those who were once alienated from politics, and at their head, women.

Before the current Arab revolutions women had little to do with politics. Those who reached positions of official power were possessed of a corrupt and authoritarian mentality or were taken by the superficial appeal of their offices. In civil society they were a little more fortunate, but in society at large women were allowed no political say or occupation. Roles were strictly apportioned along gender lines, a deficiency exacerbated by the comatose state of pre-revolutionary society in which all avenues for advancement remained shut off.

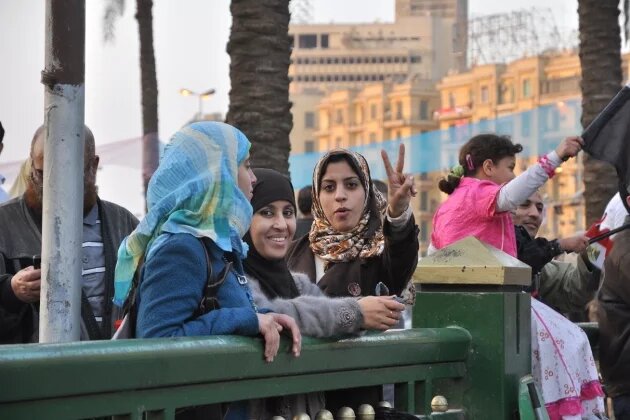

When the revolutions began, women took to the stage in unprecedented numbers. They entered politics through the demonstrations, the revolutionary activity par excellence, and though their presence and visibility in these positions varied considerably it was nonetheless genuine and undeniable. The revolutions are neither nationalistic nor class-based, but democratic, and as one of their guiding principles is the championing of human rights, it is only logical that women’s rights should be elevated with them. Women, after all, are humans, too.

This positive aspect of the revolution was not a consciously formulated position but was implicit in it. No less implicit was the revolution’s central aim— bringing down tyranny—and any attempt to highlight secondary aims, such as women’s rights was seen as a threat to the movement’s objectives. Yet this more negative corollary did not prevent women taking part with all the fervour of those who believe that they have been promised a greater role in a matter that is as important for them as it is for men, i.e.: the matter of their interest and engagement in the political life and issues of the countries where they live. Revolution is thus something that is by its very nature political and concerns everybody: it welcomes women’s participation.

Post-revolution, politics cedes to issues of power. Immediately that the central demand of the revolution has been granted the political arena shrinks and the battle for control begins. The agency of the individual is reduced to its lowest ebb. The framework within which a new legitimacy will be forged is yet to take shape and the movement for change loses its appeal. Between two worlds, it is a time in which the most organised assume control rather than the most dedicated or effective. And as long as the political struggle continues, so it remains: the preserve of the most organized and the best equipped to wield power.

If the majority of men are excluded by this process, then all of the women certainly are. Women have no experience of organised politics or of exercising power. In our current post-revolutionary, or ‘transitional’ state, the public mood changes. The Egyptian author Ezzedine Choukry Fishere describes Midan Tahrir a week after Mubarak’s resignation:

“It’s strange… The square is full of food containers and plastic bags. The youths who bustled about carrying rubbish bags have vanished. The demonstrators, with their open hearts, their organization, their music, their artistic exuberance and their clever, playful sings, have disappeared and in their place jostling crowds of unfeeling louts…’ (New Carmel Magazine, Summer 2011, p.155)

In the days that followed the mood will become more hostile. Women are not only excluded from politics, but also subjected to extreme violence, instances of which are documented by women’s and rights groups.

It’s the Algeria Syndrome. During Algeria’s revolutionary war in the late Fifties and early Sixties of the last century, Algeria’s women stood side by side with men, suffering hardship and making sacrifices. As soon as the revolution achieved its purpose, these women were sent home, gradually oppressed and marginalized and subjected to every kind of violence and discrimination. The syndrome this gave rise to is reflected in the country’s female revolutionary literature: the experience may have been a negative one, but the women accepted it.

Yet there is something else, as well. Because current Arab revolutions are not led by a single party with a formal structure and ideology, the post-revolutionary struggle for power is often surprising, incomprehensible and nebulous. The decreasing participation of women in politics, or the discrimination against them, does not manifest itself in familiar, traditional ways, though the two expressions of bigotry are linked. It takes time to understand the motives and mechanisms that lie behind this new form of bigotry. In both Tunisia and Egypt, women’s demonstrations have come under attack from individuals or small aggressive groups who scream in their faces for them to go home or get back to the kitchen, their ‘natural place’. We should also mention the wide range of activities through which Salafis express their views and positions on women.

But before we review the specific details of each country in which revolution has occurred and the size of the female contribution to those revolutions, we must pause to examine three issues of central concern to our subject: democracy, political Islam and the media.

Democracy first. It is a commonplace of the literature that democracy is vital to liberate women’s political potential, a commonplace that takes democracy to mean the people’s involvement in taking decisions over the form government and society will take, thereby satisfying their ambitions and interests. Since women are half the population, or ‘half of society’ as it’s more commonly expressed, then no democracy would allow this half to be marginalized. In fact, to strengthen their involvement would be to strengthen democracy itself. For proof, it points to the condition of women under dictatorship, which it maintains was one of servitude.

The reality is much more complex, both as regards the true nature of democracy and women’s political participation. The revolution’s stated aim is democracy, which cannot be achieved without the downfall of tyranny, but this stipulation is not enough in itself. The end of tyranny is only the first step: democracy can falter leaving the country to return to an even more authoritarian form of governance. Moreover, western democracy suffers from complications and obstructions that do nothing to help our fledgling democracy move easily and swiftly beyond its early stages.

For those who truly wish the revolution to achieve its goals, this post-revolutionary period requires a concerted, constructive, persistent and long-term movement with the capacity to last for decades. In brief, democracy is achieved through culture, or rather, by means of a civilized, cultured infrastructure; unlike the unabashed struggle for power, democracy is not a given.

Exactly the same difficulty faces women as they move to strengthen the revolution through involving themselves in politics. In fact, the task they face is doubly difficult, because they first need to unburden themselves of the violent struggle for power and the attendant process of their marginalization, induction into conflict and occasionally their outright expulsion. Central to this is the attempt to implant values and concepts of female political participation, which, as with democracy, is a long-term process that is fragile and vulnerable to setback.

Political Islam comes next. This umbrella term covers many phenomena, values and behaviours that have arisen over the last three decades, and are built around the hegemony of a literal, ahistorical Islam that stands in complete contradiction to the idea of female political participation.

The Muslim Brotherhood, an organization founded in the 1920s, is the most powerful and most organized manifestation of these beliefs. The Brotherhood’s pronouncements and actions on the subject of women in politics were once known for their hostility, but since the revolution the organization has stepped up its efforts to present a ‘moderate’ image of itself. In Tunisia and Egypt, where initial stages of the revolution prevailed, the Brothers made repeated statements in support of this ‘middle way’.

More overt in their rejection of women’s participation are all those groups and organizations grouped under the heading of Salafist, or ‘jihadist’ (in Egypt, one branch of the Salafist movement founded the Nour Party). At the head of their agenda is the implementation of Islamic Law.

Popular preachers, or sheikhs, are a third manifestation of political Islam. In recent decades these individuals have flourished, winning respect and a huge media presence, while their rulings, or fatwas, are in great public demand. They posses intellectual hegemony, to use the term in its Gramscian sense, which means a dominance they have sought and attained. There is no need here to go over the interpretation of religion advanced by these sheikhs. Suffice to say there is little variation in their basic attitude towards women, save for a few exceptions based on personal whim, a few women-friendly fatwas that do nothing to break the prevailing mould of their thinking.

Finally we have the Islamization of society itself. The reasons for this are many and the protagonists numerous: we shall not attempt to go into them here. We are concerned with the symptoms, and none is more noticeable that the spread of the hijab, and subsequently the niqab, amongst women. The phenomenon began in the early years of the twentieth century, at a time in which women were either uncovered or more and more able to be so, and further gave the impression that political Islam was a powerfully organized presence within society and could number women amongst its adherents.

The truth of the matter was that this Islamic dress code did not prevent women from going to work, nor from participating in revolutions and revolutionary activities (witness the niqab-wearing women of Yemen). Taking part in greater numbers than ever before, this participation did not occur in the framework of any Islamic group or party.

The distinction drawn between these four manifestations of political Islam, while very generalized, does allow us to see more clearly. If only partially, it helps us understand why the Brotherhood resorted to ‘beautifying’ its discourse on women, especially after the outbreak of the revolution. They were positioning themselves to appeal to a support base that they believed, perhaps rightly, was ready to accept to their religious message. Hijab and niqab-wearing women impressed by some aspects of modernity, such as seeing their sisters engaging in political activities, might be persuaded by claims that the Brothers would never stand in the way of a woman becoming president or at least a member of parliament. Furthermore, the West, with whom the country’s new political leaders would have to deal, spoke this language. Its acceptance of ‘moderate’ Islamists, at least in the early post-revolutionary period, would be dependent on the extent to which its views on female political participation chimed with those of the Brotherhood. Finally, we come to the media and the visual media in particular. The media has its own policy or approach to the issue of women and politics, albeit not a consensus. We are of course referring to the news media here, which is most immediately concerned with politics.

This media policy has two aspects: negative and positive.

On the negative side, the media limits itself to hiring pretty presenters and correspondents with scant regard for their competence or ability to present incisive analysis. This restrictive presentation offers a reified view of women that unconsciously transforms them into unthinking, untrained, objectified creatures and hinders any attempts by women to make political headway. It harms the pretty young journalist herself, because it limits her to qualifications that will disappear over time. Any experience or skill she picks up along the way will remain worthless.

Moreover, the vast majority of those invited onto these programmes to talk about politics are men: experts, analysts, opposition figures and the occasional ‘intellectual’. Women are never required to shoulder this heavy burden and as a result, viewers will never get used to the sight of woman thinking, debating or critiquing politics. It is true that this type of woman is scarce enough in reality, but it is also true that the men who make it onto the screen very rarely deserve the honour accorded them by such words as ‘expert’ and ‘intellectual’.

Superficially at least, this last point is contradicted by the exaggerated sympathy these current affairs programmes display to female celebrities, who are accorded a respect devoid of all rational or cultural justification save their celebrity status itself, i.e.: that the woman appears on television more than average. It is as though television treats politics the same way it treats advertising or drama, in other words, with a kind of inbuilt laziness that leaves it uncomfortable with all but the most familiar faces. The harm this does to women is immediate and obvious. It presents an image of the politically sanctified celebrity-woman, who has the intrinsic appeal to draw in viewers but has no real appreciation of politics or the logistical and organizational skills to make a career of it.

Along the same lines, there is the media’s coverage, presented in distinct segments, of women’s participation in the revolution, by which they mean demonstrations and protests. The stated aim of these segments is to divine the ‘extent of this participation’. We see the camera zoom in on some woman or group of women until the extent of their participation becomes grossly distorted. This is the true object of the exercise, and it is readily discovered when we view amateur YouTube footage that shows how rarely women are actually present at these events.

There is also a positive side to this coverage. None of the above has stopped the rise of highly competent, intelligent, female hosts of political programmes with excellent interviewing techniques. A number of these programmes have become famous and their reputations linked to the names of these presenters. The same is true of female news presenters who, tasked with introducing and interviewing their male guests, sometimes demonstrate a superior understanding of current events and offer a more eloquent and convincing commentary.

It goes further: the media has allowed the Arab viewer to become familiar with some of the most famous female faces of these revolutions, although it ignores some and gives others undue prominence. We have got to know Israa Abdel Fattah, Asmaa Mahfouz and Nowara Nigm from Egypt, Lina al-Monhi, Bushra Belhadj Hamida and Sanaa Bin Ashour from Tunisia, Tawakul Karman and Tehama Maarouf from Yemen and Samar Yezbek, Razan Zaitouneh and Suhair al- Atasi from Syria. All of them had their words, lectures, rants, opinions and views on air. In the quiet homes of the Arab world these women created a feeling that a woman could participate and give of her best.

The same is true of the generic footage used to divide programming. Women are given a prominence equal to men except in scenes showing military confrontations or violent repression. We have bereaved mothers, demonstrators, protestors, even rape victims such as the Libyan Iman al-Abeidi: women in every state imaginable from the days of the revolution. There is no need to list all the images here.

What follows focuses on a questionnaire that I sent using Facebook to activists, observers and analysts. Most of the recipients were old friends and the rest were more recent acquaintances. All came from Arab countries that were undergoing revolutions. The questions asked centred around the participation of women in these revolutions and the form this participation took. I devised a separate set of questions for those countries whose revolutions had attained their goals: Egypt and Tunisia. In the temporary absence of data from the field, the conclusions I was able to reach from their answers could best be described as approximate. In the vast majority of cases the answers were incomplete.

The results of my questionnaire concerned Egypt, Tunisia, Libya, Yemen and Syria. When it came to Bahrain, I had three problems: none of the Bahrainis to whom I sent the document replied, including old friends and colleagues; in the only response I did receive the author somewhat angrily wrote: “There was no revolution, just sectarian conflict!”

Finally, I only managed to gather a small sample of press clippings on Bahrain from the Arab and Western media and most of these were more agitprop than reportage. For all these reasons I decided to put Bahrain aside, particularly since the gulf between revolution and sectarian conflict could only be papered over by the most unconvincing analysis.

I divided the countries that remained into two groups: those who had succeeded in bringing down the former regime (Tunisia and Egypt) and those who had yet to achieve their objectives.

Group A: The Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions were very similar in the way they developed: both involved a series of peaceful demonstrations in which the demonstrators were met with live fire. They also unfolded in similar timeframes, with each taking roughly a month to achieve their main demand, i.e.: the departure of the president.

Tunisia: December 17, 2010 to January 14, 2011

The person who sparked this revolution by setting fire to himself and who was described as a catalyst in subsequent Arab representations of the revolution was one Mohamed Bouazizi. His suicide was imitated by others in both Tunisia and Egypt, though these individuals never achieved the status of a patriotic and national symbol.

It is notable that not a single woman followed the example of Bouazizi and his imitators, though Tunisian women engaged in many other activities in the lead up to the revolution, during the revolution and in the days that followed, with young female bloggers and activists using Facebook and Twitter to the fore. Along with their male counterparts they were proactive and well organized. Subsequently, they participated in the organization of the revolution, giving speeches and protests. They joined protests in the same numbers as the men and stood with them side by side.

The levels of participation by Tunisian women from all walks of life was the highest of all the countries, a phenomenon that can be explained by the liberationist legacy of Bourguiba’s rule, embodied in the Personal Affairs Law of 1956, the historical strength of women’s groups such as Democratic Women and Tunisian Women for Research and Development and the long experience of rights groups (The Tunisian Committee for Human Rights, founded in 1988, was the first Arab rights organization).

However, the transitional government that followed the revolution only contained two women, while the neighbourhood committees set up at the same time had no female members at all. The powerful threat to women’s political participation came from two highly capable sources: the first being groups affiliated to the former regime, who posed a directly physical threat, targeting women with the aim of chasing them off the street and out of politics; the second was the Islamist Nahda Party and the new Salafist groups.

The Nahda Party managed to manipulate its discourse on women and their gains, sometimes giving the impression that it would Islamize their legal position and repeal the relevant articles in the Personal Affairs Law, while at other times, particularly when speaking to the foreign media, denying just this and affirming its commitment to democracy and human rights.

The Salafists were more outspoken, attacking women and their political activism, especially their demonstrations for women’s rights. It may have been these groups that were responsible for telling female demonstrators to return to their kitchens.

In the current transitional period Tunisian women are engaged in a struggle over three main issues: preserving Bourguiba’s legacy in the form of the Personal Affairs Law, electing as many women as possible to the National Council, and finally, to ensure that the constitution guarantees gender equality.

Egypt: December 25, 2010 to February 11, 2011

While it is certainly true that the Tunisian revolution played a large role in determining the course of its Egyptian counterpart, especially after Ben Ali’s departure from office, and that Bouazizi’s act had a galvanizing effect on many Egyptians, it should be noted that Egypt had its own symbol: Khaled Saeed, a young man from Alexandria who was tortured to death by the police as he left a neighbourhood Internet café. The Facebook page dedicated to his memory—‘We are all Khaled Saeed’—was the spark that lit the Egyptian revolution.

Just as with Tunisia, no Egyptian woman was ever beaten to death by the police, but there was a female martyr: Sally Zahran, killed by a bullet fired towards the demonstrators. On the Internet and YouTube, women were as active as men, and perhaps the most famous clip of all was the one posted by Asmaa Mahfouz in which she called on men and women alike to throw caution aside and join the revolution. The video was popularized by her supporters and played a decisive part in attracting Egyptians of both sexes and all generations to join the revolution.

In the demonstrations, protests and violent clashes, women were as courageous as men, a courage that was especially evident in what became known as the Battle of the Camels. Their presence peaked at a third of the male turnout and their organizational and medical skills proved invaluable.

The Egyptian revolution was characterized by two unprecedented social phenomena. The first was the mixing of the two sexes: male and female demonstrators standing next to one another without a single incidence of sexual harassment, and this in Cairo, a city with a high rate of sexual harassment. The second was another kind of mixing, this time between uncovered women and those wearing the hijab and niqab, a state of affairs that gave the female component of the revolutionary demonstrations its own special flavour, transcending barriers of culture, class and religion.

The state of women’s activism in Egypt has a complex history. Women’s groups, particularly The Centre for the Egyptian Woman’s Rights and The New Woman, had a particular role to play under the old regime. This role, however, was heavily circumscribed given the absence of any prevailing ideology or overtly religious legislation, the ineffectiveness of the National Council for Women under the leadership of Suzanne Mubarak, the presence of no more than two or three female ministers in government and only four female MPs out of a total of 444, female quotas dependent on political appointments and membership of the ruling party, the Khula Law that allowed women to initiate divorce proceedings and the personal status law widely dubbed Suzanne’s Law.

Regardless, the legacy of Egypt’s intellectual enlightenment at the start of the twentieth century was divided equally between the Salafist, with its literal interpretation of religion, and the liberal, inspired by the writings of Qasim Ameen and al-Tahtawi. The majority of people oscillated between these two extremes, or at least reserved judgment until the battle was over.

Egypt’s women had early intimations that all was not well. No sooner had the army taken power than committee to amend the constitution was formed, headed by Tareq al-Bishri, a judge well known for his Islamist views and his 2005 campaign to block the appointment of Tohani al-Jibali, Egypt’s first female judge. While this committee contained not a single female lawyer or judge, it did include Sobhi al-Saleh, a leading figure in the Muslim Brotherhood, and article 75 of the amended constitution at least implied that the presidency of the republic was restricted to men only. There was only one woman in the transitional government, Faiza Aboul Naga, a former minister in Ahmed Nazif’s government under the previous regime.

Petitions poured in from all quarters to abolish the National Council for Women (even as other national councils, such as the Supreme Council for Culture, remained untouched) and there were calls to repeal the Khula Law and Suzanne’s Law.

Women were no better represented in the established political parties and not one of the plethora of new parties offered any policies or plans aimed at women, not even a road map. Only women’s associations kept their demands alive and there were a few attempts to take these issues to the streets, most notably a Woman’s Day demonstration of March 8 that called for gender equality. This demonstration was subjected to gunfire, abuse and calls for the women to go back to their homes where they belonged. During one operation to clear Midan Tahrir of protestors, 19 women were beaten, abused, accused of being prostitutes and forced to undergo examinations to determine if they were virgins.

The current battle in Egypt is between the political Islam and civil society, but it is not the only game in town. There is a third player and a much more powerful one: the army. The intellectual and cultural background to this conflict has overwhelmingly negative consequences for women: for reasons of cultural conservatism neither the army nor the Islamists welcome the presence of women in the political sphere. The liberal parties are on the whole preoccupied with the struggle for power: who will win the upcoming general elections and control the process of amending the constitution. Women’s political participation is not one of their priorities.

Group B: This includes those countries where the revolutions are yet to achieve their aims, i.e.: Yemen, Libya and Syria.

Yemen: December 18, 2010 to the present

One of the best-known faces of the Yemeni revolution is Tawakul Karman, a journalist who first came up with the idea of the Yemeni Transitional Council and one its leading members. Since 2005 Karman has been attending demonstrations in Sanaa’s Freedom Square on a weekly basis in defence of the freedom of expression. She created the transitional council in her capacity as president of Female Journalists Unchained and as a member of the Yemen Reform Assembly’s advisory council.

Yemeni women have participated in the revolution’s protests and demonstrations, in numbers no greater than ten per cent of the male turnout. Depending on the city they have either mixed freely with men or been segregated. In Taez, for instance, they can be seen walking side by side with their male counterparts, while in Sanaa they make up a separate bloc of demonstrators. This is also the case in Aden, where their turnout has been particularly poor in comparison to other urban centres.

The sharp divide between the male revolutionaries and the mostly niqab-wearing women has not prevented women from engaging in a number of other activities of central importance to the revolution, such as giving speeches, organizing activities and protests and ensuring intensive media coverage for their fellow revolutionaries.

There has been only a single female martyr in Yemen, and her death was accidental. Tribal codes and customs preclude the possibility of weapons being aimed at women, even when the security forces feel themselves under threat. This tribal structure protects the lives of Yemini women, but it also imprisons them. This hegemony is linked to the hegemony of religious attitudes towards women that is found in all Arab countries.

It is this that allows President Abdallah Saleh to openly oppose ‘illegal mixing’, a charge directed at female revolutionaries for participating in the demonstrations alongside men. As a result, many young men taking part in the demonstrations have verbally and physically assaulted female activists with uncovered hair. However the most eloquent response has come from niqab-wearing women who have protested against Saleh’s ‘fatwa’.

Anciently, Yemen was ruled by women, most famously Bilqees and Arwa, but today it is the prisoner of a tribal moral code and religious parties who require women to remain at home.

Libya: February 17, 2011 to the present

It was women who ignited the Libyan revolution. Two days before it broke out a number of mothers of Libyan political prisoners held a demonstration outside Benghazi’s main prison to protest the detention of their lawyer, Fathi Tuhail. The brutal response to this action brought Libyans into the street to demand the fall of Gaddafi. Female attendance at these initial protests varied between 10 and 20 per cent, and the women marched separately from the men.

In no time, however, the revolution took up arms and women were quickly relocated to the support lines, where they engaged in logistical activities, preparing food in particular, in addition to a little weapons training. We even saw a woman in the National Transitional Council, three women in the Benghazi Municipal Council and a woman as an official spokesperson for the revolutionaries, not to mention the young Libyan women running Benghazi’s local radio station.

The most widely known symbol of the Libyan revolution was, however, Iman al-Abeidi, who had the extraordinary courage to enter a Tripolitan hotel packed with security agents and expose her rape by a group of Gaddafi cadres. Al-Abeidi became an iconic figure and soon got her own page on Facebook: ‘We are all Iman al-Abeidi’. The image of her weeping as she made her complaint appeared in montages on Arab new channels. Libyans began referring to her as “Omar Mukhtar’s granddaughter” or “blazing a trail for women in the Libyan revolution with her sacrifice, fortitude, bravery and daring.” Al-Abeidi was elevated to this status, sanctified, because, “she had emerged from the crowds of Tripoli to tell the world that Gaddafi was a criminal, that his regime was morally bankrupt and that his glory was built on raping the free daughters of Libya.”

Her elevation to sainthood happened for the best of reasons and it drew attention to the role played by sex in the policies of Gaddafi’s regime: most notably the issue of his female bodyguards. Libyans swap stories, closer to myths, of how Gaddafi selected these women, of his treatment of them and the medieval practices he employed to maintain his control over them (one of these bodyguards later appeared on YouTube to declare her solidarity with the revolution). Nor did Gaddafi stop there. The head of the International Criminal Court, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, accused Gaddafi of distributing Viagra to his fighters in order to guarantee that his fighters would commit rape. Sexual violence is a central preoccupation of Libyans today, and it is likely that this form of persecution will later be thought of as characterising Gaddafi’s regime, given the profound effect it will have on women’s participation in politics.

Syrian women are not present in large numbers at the almost daily demonstrations up and down the country, mainly due to the extreme violence deployed against the demonstrators by the security forces and the shabiha. In gender terms, this violence is indiscriminate: there have been 51 female Syrian martyrs to date.

Where women are present they demonstrate separately from the men, except in Damascus, where the two sexes can be found marching side by side. Broadly speaking women constitute no more than 10 per cent of the male turnout.

On the other hand, women are engaged in a variety of activities on a daily basis, to support and coordinate the revolution, activities that are often more important than the demonstrations themselves. One example of this is their media work, taking videos, despatching reports and collating data. Were it not for their footage almost nothing would be known about the Syrian revolution. Not only this, but they also arrange the daily necessities that fuel the revolution: water and food. They stand in doorways to prevent the security forces from entering, they ferry snacks and medicine back and forth, break down walls and help connect houses to one another.

There is more. As in Libya, the Syrian revolution began with a demonstration by women, this time in front of the Interior Ministry, calling for the release of political prisoners. In the events that followed a number of women became well known symbols of the revolution, leading committees, talking to the media and taking on the task of recording and verifying information from the front. All these women have been to prison: some have been released and now live in hiding, others remain behind bars. Tall al-Malouhi, a young blogger who angered the regime with her writings, became an iconic figure; she is currently in prison. Suhair al-Atasi, Razan Zaitouneh and Samar Yezbek have also been to prison but are now ‘free’. Suhair is a human rights worker who keeps a detailed record of the regime’s crimes; Razan is an activist who runs nationwide coordinating committees; and Samar is a novelist who writes about the experience of both herself and others in prison and the progress made by the revolution in the field.

Syria has two societies: a traditional, conservative society and a modern urban community. At the moment, both are united in fighting the regime and trying to bring it down, but nevertheless, both operate their own distinct way. Though women from the conservative half of society take part in the revolution, they are segregated and fill traditional ‘female’ roles. The women of the modern, urban bloc are intellectuals, activists and leaders with uncovered hair.

It is clear that these Arab revolutions have motivated women to move into politics, whether by taking to streets or playing a supporting role. The majority of responses I received, even from those countries where female participation was relatively low, indicated that the revolutionary period compared favourably with the past. It is also clear that the transitional period has witnessed a regression in this political enthusiasm and that it will continue to do so, but that women are prepared to fight to maintain their status.

The battle over this issue is a two-sided affair: on one side stands the traditional-religious bloc, on the other the urban-modern-non-religious. But as the two sides come into conflict, the impact this has on women— especially the presence of hijabs and niqabs in the political arena—has caused the lines to blur. What is needed are new forms of political participation distinct from Western models.

This raises another important point. The nations of the West, where female political participation is most advanced, are not seeking to implement the tenets of modern political thought in good faith. It is their interests, rather than the principles they espouse, that determine their actions. Afghanistan stands before us as a salutary reminder. Amongst other things the military invasion of Afghanistan was going to liberate the Afghan woman from Taliban persecution, yet since the occupation this priority has slipped further and further down the West’s agenda, becoming less important with every fresh outbreak of violence between the West’s armed forces and the Taliban.

Translated from Arabic by Robin Moger.