A sculptor on the integration of intersectionality into her work and beyond.

Discrimination is often experienced on a personal level, in sometimes private, even intimate settings. What the subjects to discrimination in these moments might share is the wish for a witness, a third party, an observer. Borrowing from a vernacular expression rooted in the history of American police profiling of all Black bodies, and in reference to Charles P. Gause’s book from 2014 “Can we get a witness?” is what we ask ourselves, and the world around us.

Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s work empowers those racialized and gendered subjects, who need a witness. She defines the complexity of discrimination, with the rhetoric wit of a legal scholar, and helps those who need to make “the personal political” to borrow a phrase from the Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1960/70s. Her work helps to raise attention to discrimination and injustice beyond the personal sentiment, but actually embeds our experiences in a recognized scholarly discourse.

The intellectual framework my art originates from lies at the intersection of Black Feminist, Postcolonial, and Psychoanalytic Thought. My sculptural work thinks about relations and relationships. The ideas in my work can be applied to the small scale of interpersonal relationships, up to a larger scale of social relations. What is common throughout my works are depictions of subject-object relationships: the agent who performs an action, and the agent who experiences the performed action. Titles underline the doer and done-to dynamic: Fixator, Objectifier, Exoticizer, Manipulator, Positioner.

In my work, I try to create both positions as ambivalent and complex as they are in lived reality. And I try to create work where viewers are asked to position themselves on either side of the subject-object dynamic, and grapple with that complexity.

The term holds the complexity and psychological depth that the subjects to intersectional discrimination face. Dr. Crenshaw’s work generates a vocabulary that helps us digest these experiences, by giving them language and validity. She, alongside numerous powerful thinkers in her field, provides validity in a society where certain stories and experiences seem only be accounted for on an institutional level, once they have reached the visibility of academic discourses and university presses.

Being a Witness and making struggles visible by creating a language for them is a crucial tool for the struggling agent to be understood and the agent outside, and potentially causing the struggle, to grow empathy. Empathy with an experience that is not our own is a human value that several political gestures like solidarity are based on, and is therefore a highly productive value.

Intersectionality is not only useful in its original attempt to tie Feminist- and Critical Race Theory together, but it is useful to think of the intersection of any form of discrimination. The inclusive aspect of the term Intersectionality is where I find the great potential of it being an ageless term that will grow with time as more struggles rise to the surface of public discussions; as it already grew including struggles lite LGBTQ and gender non-binary, religious minorities, ableism, sizeism, colorism, class, and mental health issues.

During a time where “Diversity” has become an enterprise for numerous kinds of institutions, rethinking and applying the term Intersectionality to the challenge of “strategic” new hiring seems very urgent. Urgent for those 77 who hire to diversify, and for those hired to embody diversity. The way these questions relate to Intersectionality in my view is, that institutions often strategically target more than one minority marker in one prospective employee. This makes us intersectional diversifiers, so to speak.

Great potential outcomes can come of that, one might think. Since our approaches as intersectional diversifiers do not target one struggle, in ideal instances we can build a more cross-compatible mass. And at the same time we can “on paper” be read as door openers for larger pools of minorities, given our multi-facetted identities.

Where I see the greatest challenge is in going beyond a mere embodiment of diversity, but actually challenging the institutional structure with the politics that are attached to our respective diversity markers, and by our respective intersectional lenses. We don’t just come in a body, but we come with politics.

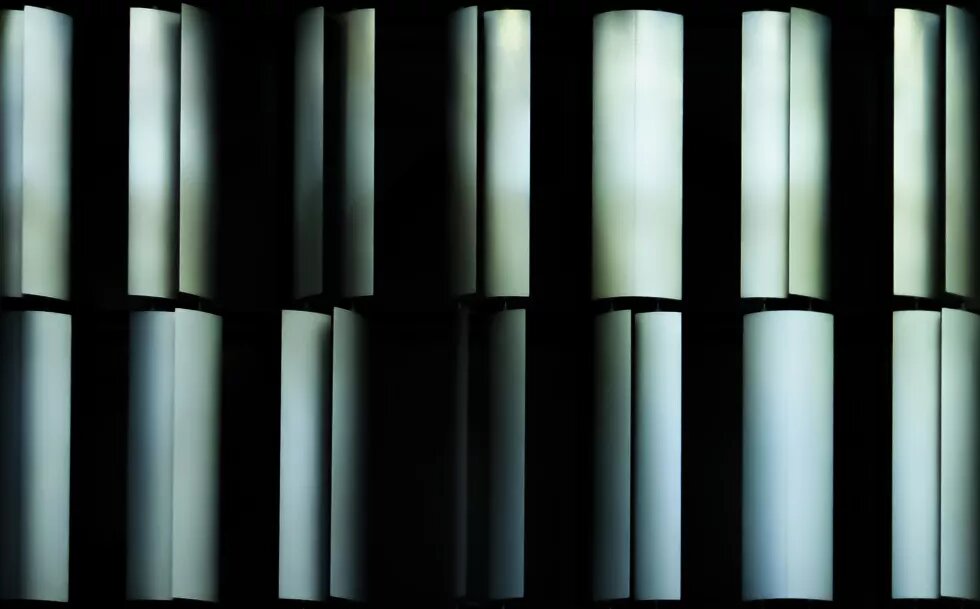

Diversity can be more than a politically correct gesture. In my mind, it can be a sincere attempt to structural change. And the more intersectional diversity, the greater the chance that all columns of the structure, the house, the institution get thoroughly and collectively destabilized, reconsidered, updated, and freshly installed—for it to be done again and again.