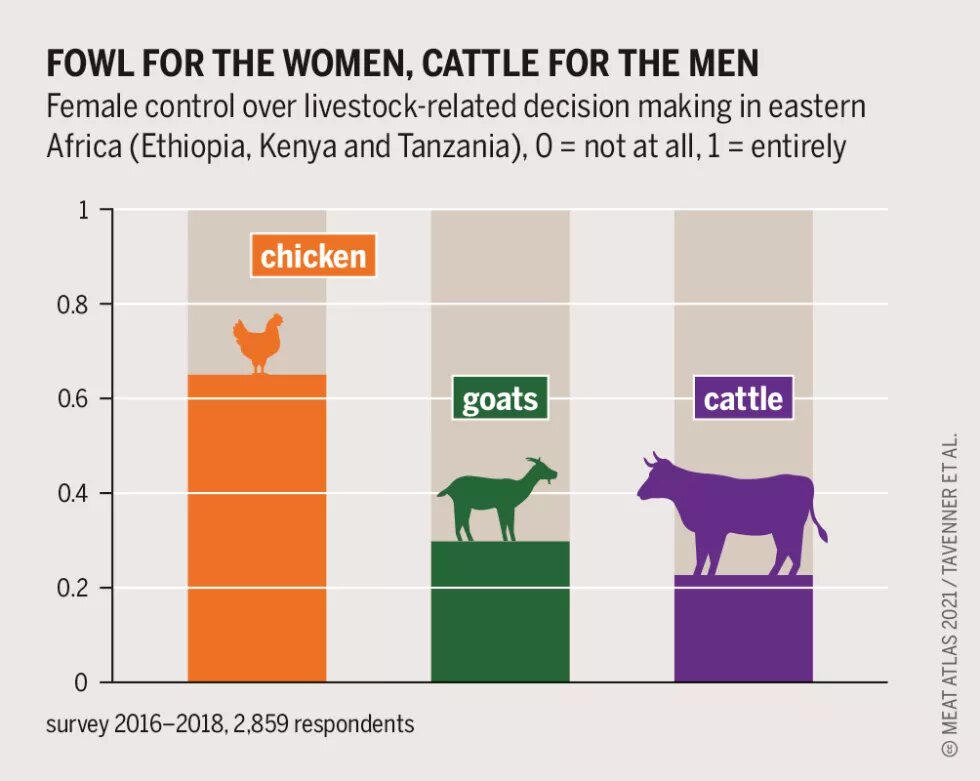

In many countries, women do most of the farm work, but they are not allowed to make most of the decisions. They have to balance caring for their children and elderly parents with looking after the chickens and goats. Livestock can be a welcome source of extra money, but may also mean more work. And if selling eggs and milk becomes more profitable, men very often take charge.

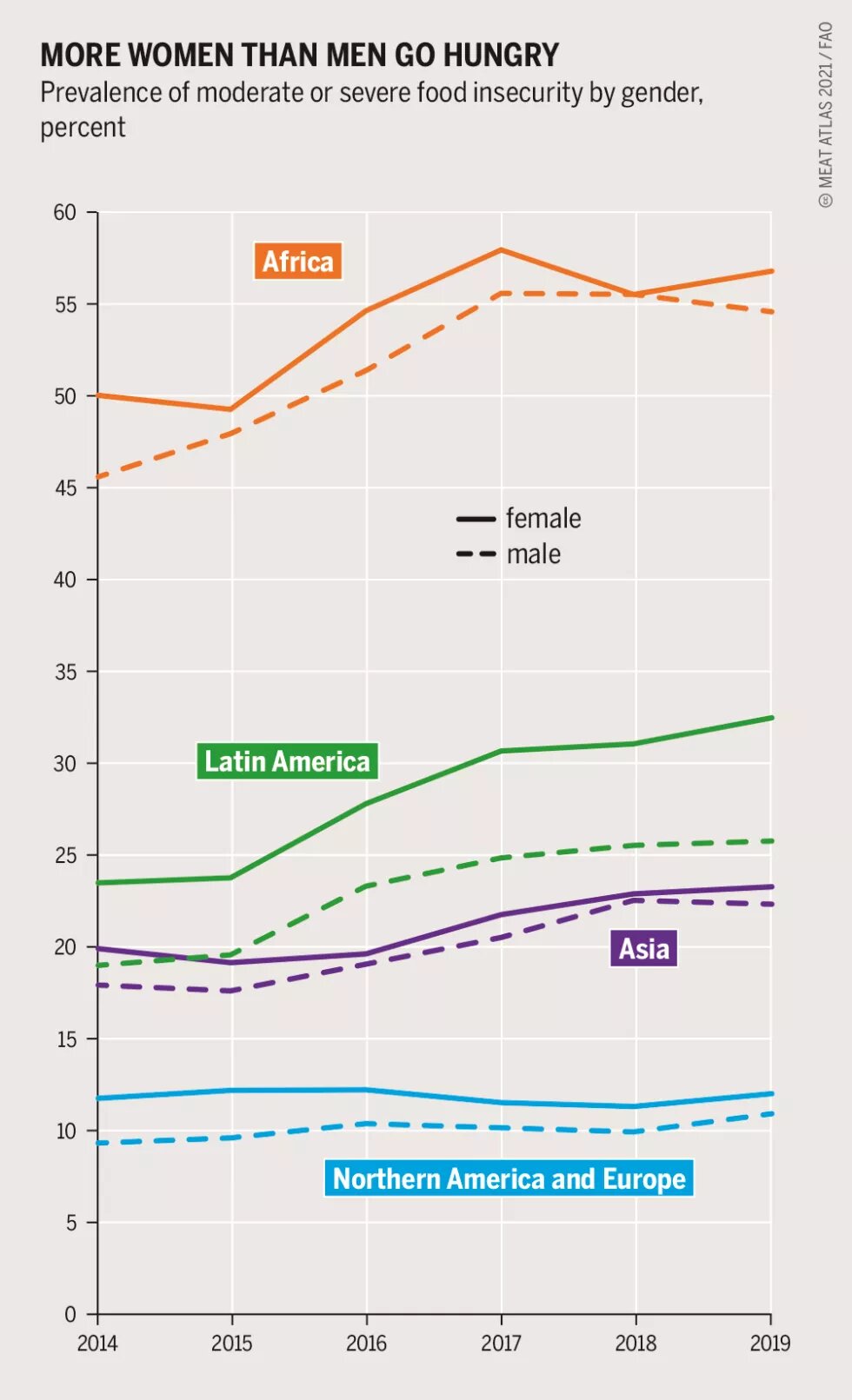

Small-scale livestock rearing is an important livelihood for many women in rural communities. The World Bank calculates that one in five people around the world rely on livestock as their main source of income. Almost two-thirds of the world’s 600 million poor livestock keepers are women.

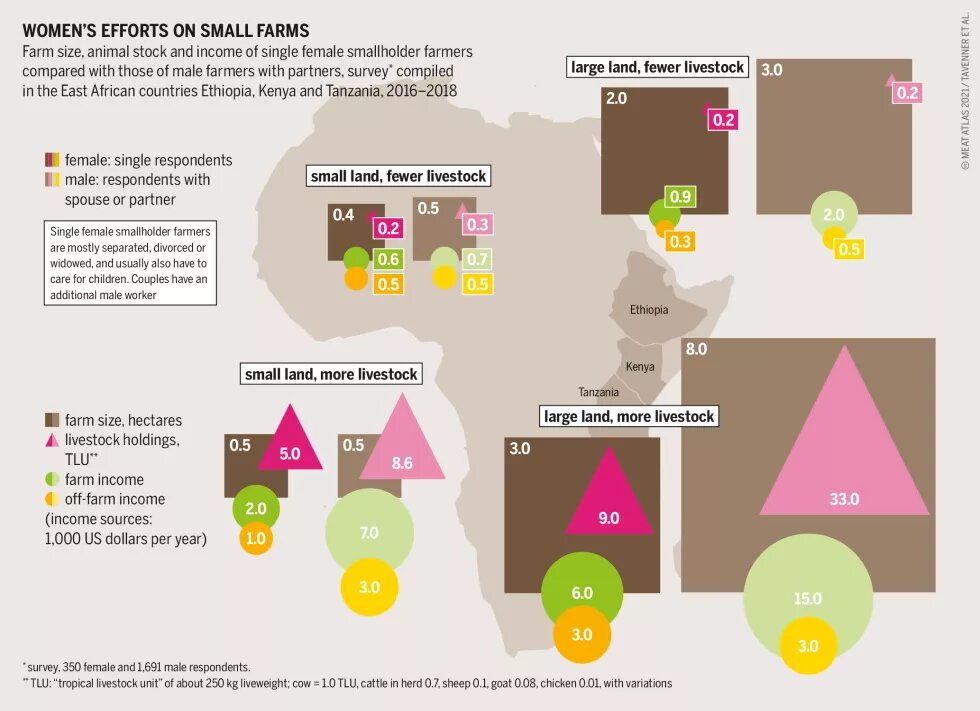

Women’s roles in livestock keeping differ from region to region, and who owns livestock – men or women – is strongly dependent on social, cultural and economic factors. The ownership also depends on the type of animal. Women make up the majority of poor livestock farmers who raise sheep, goats and Poultry. They have limited access to services, land and capital. But when rearing these animals becomes a more important source of family income, their ownership, management and control are often turned over to men.

A dairy intensification project in Tanzania shows the importance of considering gender in value chain development and reveals the complex interplay between intensification, empowerment and child nutrition. The project successfully increased milk production by smallholders. But as soon as higher yields made milk a marketable product, its control moved to men. Women’s control over both milk and income decreased, and the nutrition of children did not improve.

Structural barriers, gender stereotypes and discrimination may exacerbate the position of women in livestock-related livelihoods. These barriers are maintained through social norms that deter women from making decisions, travelling to markets or turning to extension agencies for advice. They deny women access to using, owning or inheriting land and livestock, and prevent them from obtaining resources such as credit.

The problem is widespread. A survey by the International Livestock Research Institute found that in low- and middle-income countries, women made up the majority of the poor livestock farming workforce. But they accounted for under 19 percent of agricultural holders, and received only 10 percent of total agricultural development funds and 5 percent of all agricultural extension services. In Senegal, according to a study by the think tank IPAR, women own just 13 percent of the land and were granted only 1 percent of loans for agriculture because they lack titles to the land they farm. The Global Forest Coalition made similar findings in Latin America: in Colombia, only 8 percent of the women interviewed owned land, compared to 17 percent in Paraguay, 20 percent in Bolivia, and 40 percent in Chile. Indigenous women, household heads and young women may also be discriminated against not only because they are female, but due to their age, ethnicity, status or gender identity.

Because they lack access to production resources, women are likely to be poor and not have enough to eat – even though they devote over 70 percent of their income to household needs. Livestock are one of the few farm resources that women can own and control. They provide nutritious food each day that women can use to feed their families. In areas where it can be hard to earn money in other ways, women can sell live animals, meat, milk or eggs to earn money to pay household expenses.

In many places, women and men typically have different tasks, with women and girls taking on a greater share of unpaid work such as childcare and domestic chores. This can worsen inequality and poverty for those who work with livestock. Even though the animals may be a source of income, they add to the women’s workloads. The extra burden may mean they cannot go to school or attend training, which in turn harms their ability to earn money or take part in making decisions in their communities. In one anti-poverty program described by the UN Secretary-General where households were given livestock, the women ended up spending 217 percent more time on the animals – an extra 415 hours a year.

Deforestation in the Amazon and other areas is on the rise because of the need to produce meat and soybeans for global markets. That has reduced local communities’ rights to the forests and land. Given that women rely heavily on these and other natural resources – in order to raise livestock, for example – such deforestation and environmental degradation has had a big impact on them.

The economic and social empowerment of women who keep livestock depends on a range of factors: securing their land tenure rights, addressing the burden of unpaid care work, improving their access to education and basic services, and ensuring they can use forests and other natural resources. It is not possible to achieve food security and more sustainable food systems without involving women in planning, decision making and implementation. Guaranteeing women’s ability to engage in small-scale livestock farming will help them secure steady incomes and a supply of clean and nutritious food. That will in turn help close the gender inequality gap.

This article was first published by HBS Brussels.