Women’s political participation is making slow progress, while the overall record of the NLD government on women’s rights remains ambivalent.

Mostly men are influential in assuming political leadership in Southeast Asian nations, but Myanmar has become one of a few Southeast Asian nations that have a woman leader.

After decades of military rule, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi emerged as a woman leader during the pro-democracy uprising in 1988. As the undisputed leader of the National League for Democracy (NLD), he has gained support and love from the citizens ever since. She is the daughter of General Aung San, Burma’s independence hero who gained wide support from the citizens but was assassinated in his thirties.

At the beginning of the 1988 pro-democracy uprising, a letter circulated, claiming that the eldest son of General Aung San would provide leadership in the uprising. Nobody knew which group circulated the letter. But, surprisingly to many, the person who emerged as a leader of the people at the time was Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. Her brave words in her first public address delivered at the west archway of the Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon met with thunderous applause. Originally, the general public supported her just as a daughter of General Aung San. But her high caliber actions and thinking attracted more supports of the citizens, and she became a public leader.

A Female Leader, Restricted

As a result of the democratic uprising in 1988, elections were held in 1990 and won by the NLD, but the result was never accepted by the military. The junta that continued to rule imprisoned many students and citizens who demanded democracy. They suffered both physical and mental torture in the prisons. As for Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, perhaps because of her deceased father’s clout or being a women or being an international icon, she was not tortured physically during her house arrest. But her personal life and being a woman attracted those who wanted to make personal attacks against her. They tried to humiliate and defame her in various unfair ways. Whatever they did, however, their efforts were not effective because of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s mental strength.

The military-drafted constitution valid since 2008 imposes specific restrictions that forbid Daw Aung San Suu Kyi from becoming the president of Myanmar. Her supporters have tried to amend the relevant clause, but to no avail. When the NLD won the 2015 elections, by creating the position of a “State Counsellor”, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi overcame this obstacle and became the de facto leader of Myanmar since 2016.

So, generally, Myanmar can be seen as a nation led by a woman. Was being a woman the reason why her political route was tougher? Did the military, which was influenced by patriarchy, unfairly treat her, feel jealous of her and hold grudges against her? Or did they give her fairer treatment? Neither Daw Aung San Suu Kyi nor any observer has spoken out publicly about this.

Some critics of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi have argued that, under her government, women's affairs has been reduced to an insignificant priority. One of the reasons behind this accusation is that her party refused to accept the demand for a 30 percent women’s participation in important roles of the party. Under her government, women’s participation in the cabinet and political decision-making is still very limited. Women’s participation in important roles under her government is somewhat greater than the participation under successive military juntas, as there were two female chief ministers on state and regional levels, and a significantly increased number of women leaders participates in lower-level administration and even in the Union Electoral Commission. Still, some people continue to call for increased women’s participation in the government leadership. Since the times of the previous military junta, most director-level officials in the government departments are military-turned-civilian officials, and this contributes to the fact that women’s participation still remains small.

Women in Parliaments

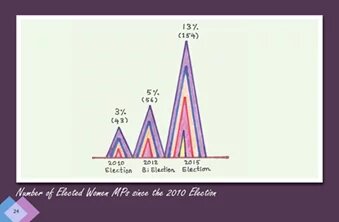

At the same time, however, the NLD has carried out a policy to promote women’s capacities in the party. Women and young people have been given higher priority to be selected as the party’s parliamentary candidates. But the party has been giving first priority to those who are highly capable. Overall, women’s participation in parliament has increased gradually. Three was a mere 3 percent women’s share of parliamentary seats in the 2010 general elections; 5 percent in the 2012 by-elections; and 13 percent in the 2015 general elections. Although the figures have become larger, women’s rights activists continue to maintain that the number is still not adequate.

The daily lives of the women in parliament are not easy. The Union-level MPs of Myanmar have to live in the new capital Nay Pyi Taw, so most of them have to live far away from their families. As for MPs who are mothers, they cannot be happy to live away from their children. In all parliaments including regional parliaments, the majority of the MPs are men, so women MPs have to take more serious efforts in order that their ideas and opinions are admired. In trying to draft or amend laws related to women’s rights, they have to debate fiercely with male MPs in order to gain their support for the laws. Some of their efforts succeeded, such as setting the minimum age of marriage to 18 years (instead of the customary law age of 15 years). But others were not fruitful, especially the initiative for a bill on prevention of violence against women, drafted since the days of the Thein Sein government (2011-15), but still not ratified under the NLD government as some points have remained unacceptable to many men.

Not all women MPs focus on women’s rights. Some women MPs do not want the people to think that they will work only for the sake of women’s rights – and we cannot blame them for that. In fact, women’s rights will be achieved only if both women and men work cooperatively. And both women and men need to be interested in other matters too, and need to be given the relevant rights. It is gender equality that we need.

Improving Political Participation

Since 2012, Phan Tee Eain has devoted sustained efforts to promote women’s meaningful participation in nation building and to achieve gender equality. Phan Tee Eain has also observed women’s participation in elections. About 150 women candidates stood for the 2010 general elections, and about 800 stood for the 2015 general elections. 1,112 women candidates will contest the upcoming 2020 general elections. Although we now cannot know how many women candidates will be elected, it is a hopeful situation that women are trying to get the opportunity to participate in nation building; getting ready to face difficulties in politics; and gaining self-confidence. But women’s share among the candidates is just 16 percent, so it is just a small improvement.

Table – Number of Candidates for 2020 General Elections

In an interview, a reporter asked Phan Tee Eain: “What do you expect them to do if there were more women in parliament?” And we answered: “We hope that they will be able to participate in all aspects of national affairs, even for the peace.” Only when differing strengths of both men and women are used cooperatively in all areas, there will be great development.

If we have more women leaders, it should become easier to introduce laws to protect women more quickly and effectively. But without men’s eager cooperation, without their respect for women, and without their understanding of women’s needs, no law can effectively protect women. Our hope is not to gain women’s overwhelming parliamentary votes in favour of women’s rights and relevant policies. Our hope is that women MPs can strongly represent women’s voices, and to gain more opportunities to make negotiations and discuss women’s opinions in order to make men understand more about women’s rights.

We firmly believe that only peace based on discussions and mutual understanding is meaningful.